Derek Turner writes …

Compare these two counterfactual claims:

(1) If the dinosaurs had not gone extinct 66 million years ago (mya), then at least one lineage, such as Tröodon, would have eventually evolved into big-brained, highly social, linguistic, technology-loving bipedal “dinosauroids” that are rather like us.

(2) If the dinosaurs had not gone extinct 66 mya, then humans (that is, our particular biological species) never would have evolved.

I don’t know about you, but I have completely different intuitions about these two hypotheses. Claim (2) sounds really plausible to me. Claim (1), on the other hand, leaves me scratching my head. It might be true, but it also seems extraordinarily speculative. Nor is this quite the same kind of speculation that Adrian Currie defended in his recent essay; Adrian was interested in speculations about the actual past—for example, about actual dinosaur behavior. Claim (1) involves speculation about alternate prehistory, about what might have happened if things had been different. Anyhow, speaking for myself, I am inclined to think that claim (2) is very probably true, but I’m not inclined to believe claim (1) at all. I’m basically agnostic about (1).

Maybe you have different gut reactions to these two claims—and if so, then that itself is something interesting to think about. But my own intuitive judgments here leave me with something of a philosophical problem. Claims (1) and (2) are, in a certain sense, in the same boat: Both amount to “what if” prehistory. So what is it, exactly, that makes claim (2) more credible than claim (1)? I’ll come back to this philosophical question in a bit, but first some context.

Both claims (1) and (2) have been defended by serious professional paleontologists. In his 1989 book, Wonderful Life, Stephen Jay Gould defended a version of claim (2):

“We came this close (put your thumb about a millimeter away from your index finger), thousands and thousands of times, to erasure by the veering of history down another sensible channel. Replay the tape a million times from a Burgess beginning, and I doubt that anything like Homo sapiens would ever evolve again.”[1]

Presumably, the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction event 66 mya is just one of those “thousands of times” that Gould has in mind. The “Burgess beginning” here refers to the Cambrian explosion of multicellular life that began around 542 mya. I will just go ahead and say that Gould (who is an intellectual hero of mine) seems to me to get things just right in this passage.

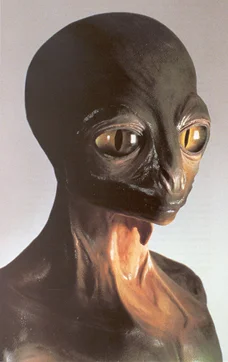

On the other hand, though, some serious people also take speculations about dinosauroids very seriously. We owe the term “dinosauroid” to a paper by Dale Russell and Ron Seguin published in 1982. Russell was a paleontologist and Sequin was the sculptor who created the model pictured above. Russell and Seguin imagined the dinosauroids to be very like us, but with a few differences: they'd communicate using a language based on birdsong, and would regurgitate food for their babies. Russell always acknowledged the speculative nature of this idea, and only promoted it as a kind of thought experiment. But the idea had some basis in the observation that at the end of the Cretaceous, just before the big cataclysm, there was a striking upward trend in the encephalization quotient (or EQ) of Tröodontid dinosaurs. The EQ is one way of measuring the relationship between brain size and body size. Interestingly, Simon Conway Morris, the Cambridge paleobiologist who has emphasized the importance of convergence in evolutionary history, comes across as an incautious dinosauroid enthusiast in this BBC special. Paleontologist Darren Naish has a lovely discussion of the history of the dinosauroid idea on his blog. Naish points out that as we revise and update our views about dinosaurs, we might also need to update Russell’s counterfactual speculation. Instead of a scaly, reptilian dinosauroid, perhaps the small therapod dinosaurs would, if given the chance, have evolved into the more birdlike Avisapiens.

So, with that context in place, what accounts for the difference between claim (1) and claim (2)? This is where a little bit of philosophical analysis goes a long way. Even though both of these claims are counterfactuals—and even though they both have the same antecedent—they are actually very different kinds of claims. Consider the difference between the following:

(1*) A prevented C from happening. So if A had not happened, then C would have happened.

(2*) A enabled C to happen. So if A had not happened, then C would not have happened.

The relevant distinction here is between enabling conditions and preventing conditions. The mass extinction 66 mya was a preventing condition for the evolution of dinosauroids, but an enabling condition for the evolution of humans. This difference between enabling and preventing conditions should bear on our assessment of the counterfactuals. If A is really an enabling condition for C, and if you remove A, then C can’t happen. So the only issue with respect to counterfactual (2) is whether the K-Pg mass extinction was indeed an enabling condition for the evolution of humans. It seems really plausible to me that it was (though it’s an interesting question how one might try to back this up). But where A is a preventing condition for C, removing A doesn’t really tell you whether C will happen. All it does is open up the possibility of C happening. So if the K-Pg mass extinction was a preventing condition for the evolution of dinosauroids, removing that preventing condition just leaves us with a scenario where the possibility of dinosauroid evolution is opened up. Maybe the dinosauroids will evolve, and maybe they won’t. This difference between preventing and enabling conditions means that prehistoric counterfactuals are not all in the same boat.

In one excellent recent paper on historical counterfactuals, philosopher Daniel Nolan observes that “an important source of hostility to using counterfactuals in history is based on the suspicion that we cannot tell which counterfactuals are correct, if indeed any are.”[2] Nolan then proceeds to argue that counterfactual thinking might still be useful even if this suspicion were correct. However, the distinction between preventing and enabling conditions suggests that we sometimes can tell which ones are (probably) correct and which ones are out there on the speculative limb. Stephen Jay Gould’s claim (2) is probably true. But we don’t have much reason to believe the claim (1) about dinosauroids.

This post just barely scratches the surface of a rich and exciting philosophical topic. If you find these issues as interesting as I do, you might enjoy Rebecca Onion’s recent defense of counterfactual history in Aeon magazine. Or take a look at Daniel Nolan's terrific paper (reference below). Paleontologist Brian Switek also has a great essay on dinosauroids. Switek places the dinosauric discussion in the context of the Gould/Conway Morris debate about evolutionary contingency. Avi Tucker has an interesting discussion of historical counterfactuals in his book on the philosophy of history and historiography, Our Knowledge of the Past (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

[1] S.J. Gould, Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. New York: W.W. Norton, 1989, p. 289.

[2] D. Nolan, “Why historians (and everyone else) should care about historical counterfactuals,” Philosophical Studies 163(2013): 319.