We’ve talked before about the importance of comparative reasoning in anatomical reconstruction. (Please read “Problematica”!) Well, it just so happens that there have been some splendid examples in the news lately.

The first comes from the journal Diversity, where Russell Engelman of Case Western University just chopped Dunkleosteus in half relative to previous estimates of maximum body length. Dunkleosteus, if you don’t know, is an armored placoderm hailing from the Late Devonian. It has, I submit, the ugliest mug of any fish in the fossil record. (For real. Check this thing out.) Previous best guesses placed its maximum length around 5–10 meters, with most estimates settling near the upper end of that range. But according to Engleman, this is too high. His claim is based on a new proxy for body size: orbit-opercular length, which corresponds to the distance between the anterior margin of the eye socket and the posterior margin of the head. The measure fulfills three desiderata for a body length proxy for Dunkleosteus: (1) it accurately measures body length across fishes in general, (2) it is measurable on arthrodire* fossils, and (3) it accurately predicts body length in complete arthrodire specimens. (Arthrodira is the group that includes Dunkleosteus.)

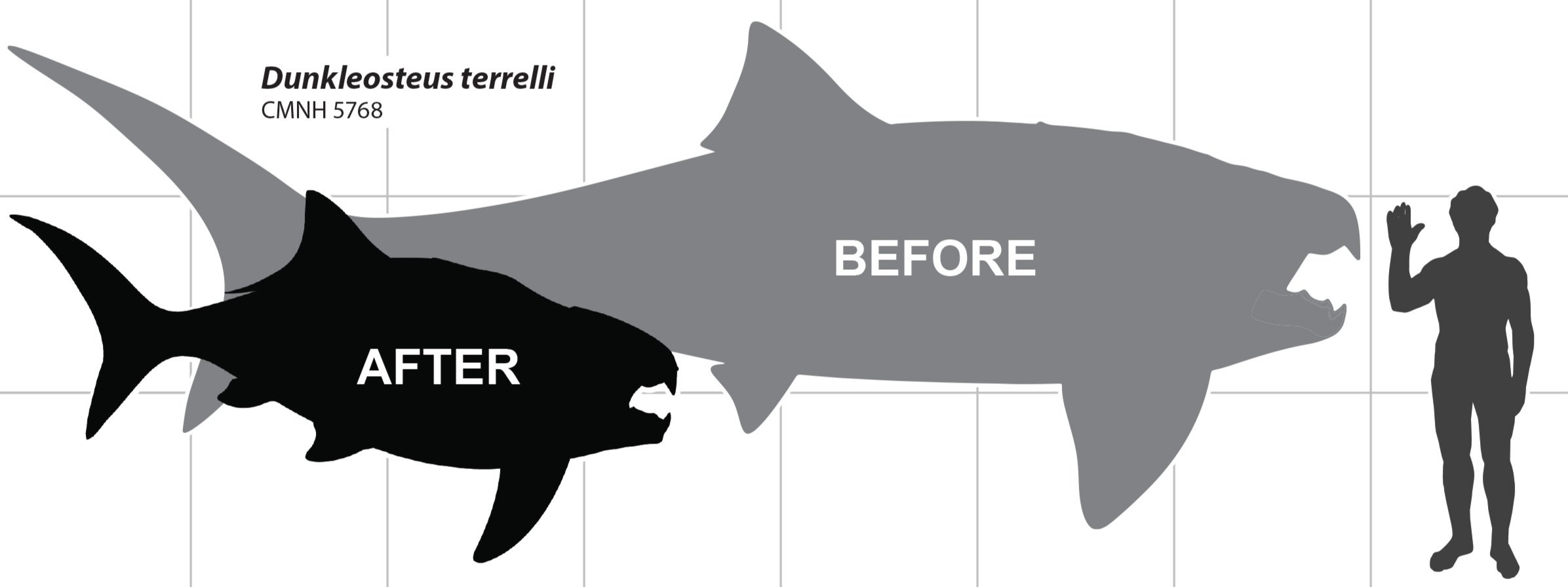

The results of Engleman’s analysis are most vividly expressed in the graphical abstract reproduced above. If you prefer it in writing: large arthrodires like Dunkleosteus “were much smaller than previously thought,” with the largest known individuals probably reaching lengths of no more than ~4.1 meters (13.5 feet). Moreover, “[the] length estimate for Dunkleosteus… result in an animal with a very deep and wide body relative to its total length.” (#Chunkleosteus) This body type is consistent with other arthrodires whose proportions can be more directly figured, but even still Dunkleosteus is an “extremely girthy” outlier. Nothing like it exists in the present oceans, although lungfish, coelacanths, and tuna provide the closest living analogs.

At this point you might be justifiably upset that reanalysis tends only to diminish the size of iconic paleontological monsters. (This is the third example of this phenomenon I have discussed, in addition to the two in this installment of “Problematica.”) But happily, a reanalysis of the sauropod Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum demonstrates the expansive power of the practice. M. sinocanadorum is known from a single specimen, and this a highly incomplete one. Yet fortunately for researchers, the probable sister taxon of M. sinocanadorum provides a useful model for estimating the length of its neck.

Life reconstruction of M. sinocanadorum. Credit: Júlia d’Oliveira

Here’s where things get fun. The sister taxon, Xinjiangtitan, has the longest preserved neck of any known vertebrate, measuring just under 13.5 meters (about 44 feet). For comparison, that’s about the length of an adult male humpback whale. But based on “functional centrum length measurements” (which measure the distance between the two points at which a centrum articulates with an adjacent centrum), researchers were able to derive a simple scaling factor that puts the M. sinocanadorum neck at 14.4 meters! When they further adjusted the figure to factor in allometry, this jumped to 15.1 meters (nearly 50 feet), which they describe as a “conservative” estimate. As Jack Tamisiea* observes, “This would account for roughly half of its estimated total body length and is equivalent to just over eight giraffe necks stacked end-to-end.”

[* Jack Tamisiea has you covered. Here is his story on Dunkleosteus.]

Reanalysis is not simply an exercise in diminution, then. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away: and so it goes with paleontology.