One thing that's always struck me about the paleontologists I've followed is how each seems to be a relatively competent artist. I've always taken this to be a function of outreach: paleontologists know how effective a cool drawing of an extinct critter can be for inspiring public interest. After a few days in the field, I'm now convinced it's a skill that comes with having to maintain a field notebook.

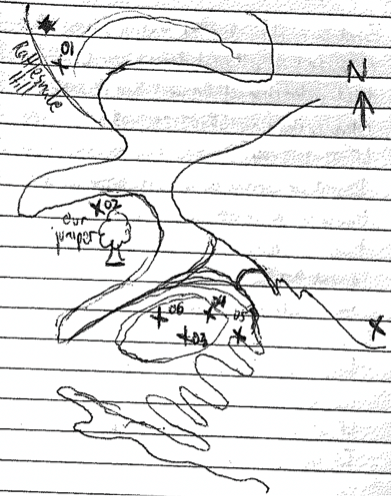

One of the author's field sketches.

It really is true that a picture is worth a thousand words. (This is especially true when an author isn't sure which words to use, as may be the case when the author is describing anatomy nine weeks before starting an anatomy course.) When you're in the field and the sun is doing its normal murderous thing and you have a van to catch in an hour or else you'll have to stay out in the field with the murderous sun and fossils and coyotes, drawing a picture can be a lot more effective than writing out those thousand words. As it turns out, the field notebook is a much more visual medium than I initially expected.

I've used pictures in my notebook for two purposes. The first is to communicate fossil locations with maps. The second is to communicate fossil shapes and relative positions for preparators back home in the lab.

One of the author's field notebook maps. Obviously as good as Google makes 'em.

I'm not good at the maps.

After drawing half a dozen fossils, however, I'm feeling a bit more confident in those.

Another fossil sketch with directions indicating where particular fragments have been stored.

Actual fossil depicted in sketch above.

None of these will pass muster for a textbook--hell, they're vaguely embarrassing for a blog post--but they're good enough to communicate information such as, "what did this look like when it was found?" or "how does the stuff in this collection bag relate to the stuff in that collection bad?" or "should I blame geology or the paleontologist for this mess?" Learning the necessary technical lingo would obviously help, but what language could be more standardized than pictures?

NOTE: epistemologists and philosophers of language should take that question as rhetorical.