* Jan Forsman is an adjunct assistant professor and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Iowa. His research is on early modern women philosophers and skepticism, but he also writes about the history of paleontology…

Although paleontology studies all kinds of extinct creatures, most people only tune in for dinosaurs. New mass and size records, evidence of parental care, and novel interpretations of iconic beasts like Tyrannosaurus rex are especially titillating to the general public. The possible return of Brontosaurus to scientific legitimacy was likewise a news item several years back.[1]

Even though fossil evidence is often fragmentary, dinosaur research is racing ahead. In a spectacular development, researchers have recently gained the ability to reconstruct the color of certain dinosaurs from preserved melanosomes in skin and feathers.[2] At the same time, many new specimens have added greatly to our knowledge of dinosaur evolution, particularly in its early stages.[3] No doubt mistakes have been made that will need to be corrected, but on the whole this is an exciting period in the history of dinosaur paleontology.

The history of paleontology contains many examples of outstanding success. Yet it is also full of missteps and mistakes, especially in the early days. One of these oddities concerns the first ever named genus of non-avian dinosaur. The story includes a missing fossil, speculation about giant humans, a theory of procreating stones, and a possible dinosaur named after a human ball sack. Welcome to the weird history of paleontology.

Big Lizard in the Backyard

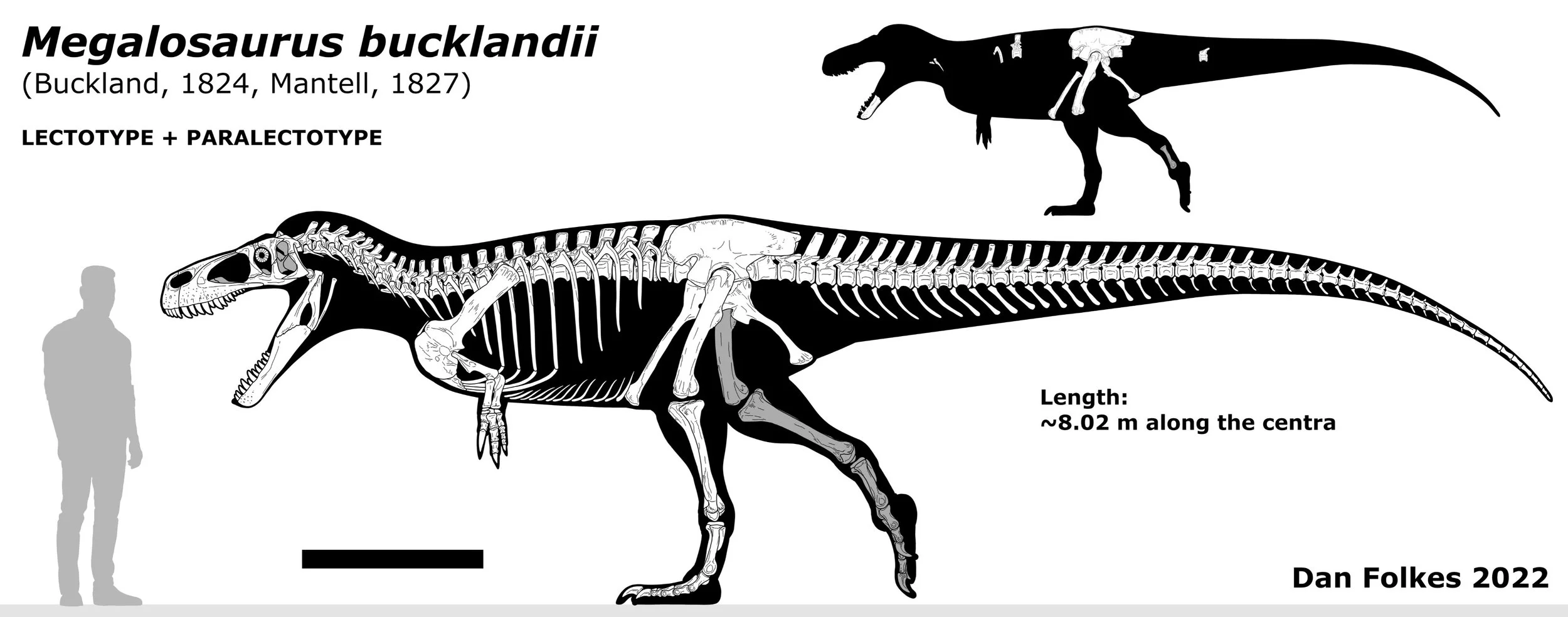

The first officially named dinosaur genus is typically said to be Megalosaurus (from the Greek megas for great, and sauros for lizard), of which William Buckland (1784–1856) published a description in 1824. At the time, the term “dinosaur” did not exist, and Buckland called the creature “an enormous fossil […] reptile,” speculating that it was probably “an amphibious animal.”[4] Today we know that Megalosaurus was a land-dwelling carnivorous theropod, around six meters long.

Engraving of the lower jaw of Megalosaurus, based on the specimen discovered in the Stonesfield Slate of Oxfordshire. (From William Buckland’s Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield)

Buckland’s amphibious interpretation is understandable, given that previously identified fossil reptiles were almost exclusively marine organisms.[5] Georges Cuvier (1769–1832), renowned as the father of vertebrate paleontology, stated in 1808 that the remains found in Maastricht, Neatherlands, belonged to a giant water-dwelling monitor lizard, which William Conybeare later named Mosasaurus.[6] Fossil hunter and paleontological trail-blazer Mary Anning (1799–1847) found the first full skeletal fossil of the fishlike Ichthyosaurus as a 12-year old, and in 1823 discovered another well-known marine reptile, Plesiosaurus (both named by Conybeare and Henry De la Beche [1796–1855]).[7]

Such findings inspired scientists to theorize about how the earth might have looked before a single human had set foot on it, while simultaneously raising questions about the relations between groups of animals. Although both Conybeare and Buckland were clergyman who denied evolutionary development, public interest in such questions created intellectual space for the notion that certain species might expire while others might develop into something else.[8]

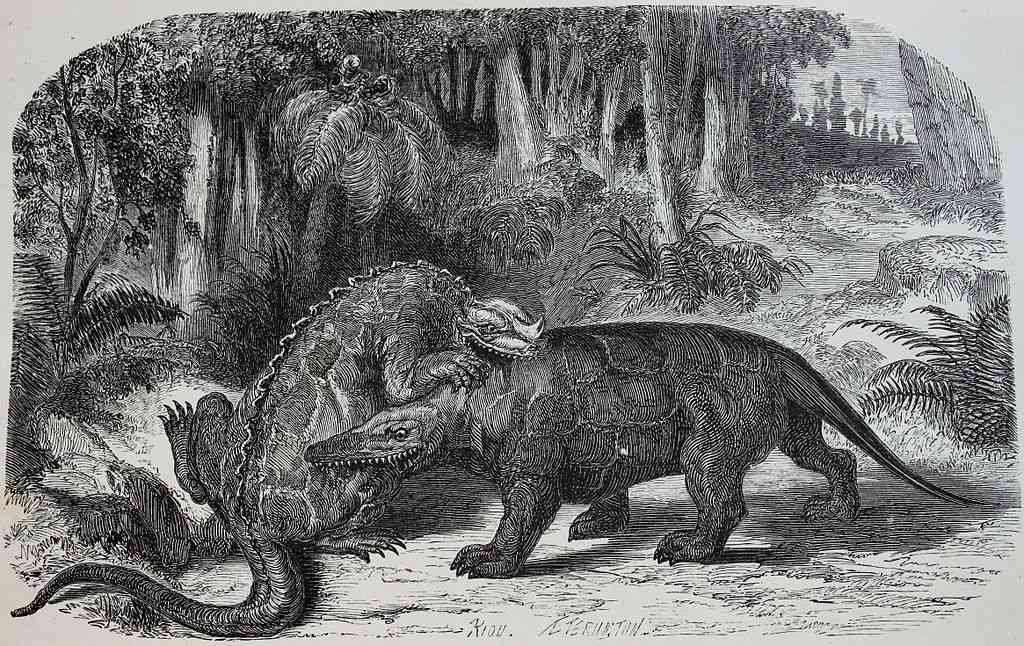

Typical of his generation, Buckland did not assign the Megalosaurus specimen a species name, christening only the genus. Megalosaurus did not get a type species before 1827 when Gideon Mantell (1790– 1852) included its remains among his geological study of the southerneastern part of England under the name Megalosaurus bucklandii (Buckland’s Great Lizard).[9] Fifteen years later, Megalosaurus was one of three genera that Richard Owen (1804–1892) used to define the group Dinosauria (the other two were Hylaeosaurus and Iguanadon, both named by Mantell). This further ignited speculation that these creatures were not just big lizards but a distinct kind of animal.

Megalosaurus squares off with its presumed prehistoric foe, another early dinosaur discovery, Iguanodon. (From Louis Figuier’s Earth Before the Deluge, 1865)

A Bone to Pick with Dr. Plot

Fossils of extinct animals have been known since the earliest days of recorded history. In ancient Greece, giant bones were often taken to be the remains of legendary heroes and demigods. King Pelops’s lost “shoulder blade” was described as massive and Herodotus (c. 484–435 BCE) reported that when the Spartans discovered the bones of Orestes, the son of King Agamemnon, his skeleton was over 10 feet high.[10] These bones are now thought to have belonged to large Pleistocene mammals, such as mammoths or mastodons. Stories of one-eyed cyclopes are sometimes thought to have been inspired by Pleistocene dwarf elephant fossils of the Palaeoloxodon genus, and extinct terrestrial and marine creatures have likely fed into stories about dragons, leviathans, and other monsters from ancient China to the Americas to Medieval Europe.[11]

The history of Megalosaurus similarly stretches all the way to the end of the 17th century. The first known fossil, part of the femur, was found in the Taynton Limestone Formation in Cornwall, England, in 1676. A year later, English naturalist and historian Robert Plot (1640–1696) described the fossil in his work Natural History of Oxford-shire (1677). The work was renowned in his time and Plot received fame and accolades because of it. He was elected to the Royal Society of London in its publication year and in 1684 became the first professor of chemistry at the University of Oxford, as well as the keeper of the Ashmolean Museum.[12]

Robert Plot

Plot did not regard most fossils as the remains of once-living organisms, but instead as mineral salts crystallized into coincidental shapes and forms. In the case of the Cornwall specimen, however, he correctly identified it as a part of a femur and wrote about it at length. Although the specimen was larger than the femurs of “both horses and oxen,”[13] Plot rejected the suggestion that the bone could have grown to its gargantuan size while in the ground. Some of Plot’s colleagues estimated that the femur could have belonged to an elephant “brought hither during the Government of Romans in Britain,”[14] but Plot did not regard this as a credible theory either. (There were no sources in Plot’s time that indicated that the Romans brought elephants to Britain, and after comparing the specimen to real elephant bones in 1676, he found there to be significant differences between the two.)[15] This led him to conclude that the bone belonged to a giant human, reminiscent of the Titans of Greek mythology. He even dedicated a few pages of his work to describing the history of such giants, including some contemporary lore, mentioning a Dutch woman “seven foot and a half high, with all her limbs proportionable”[16] that he had observed in Oxford.

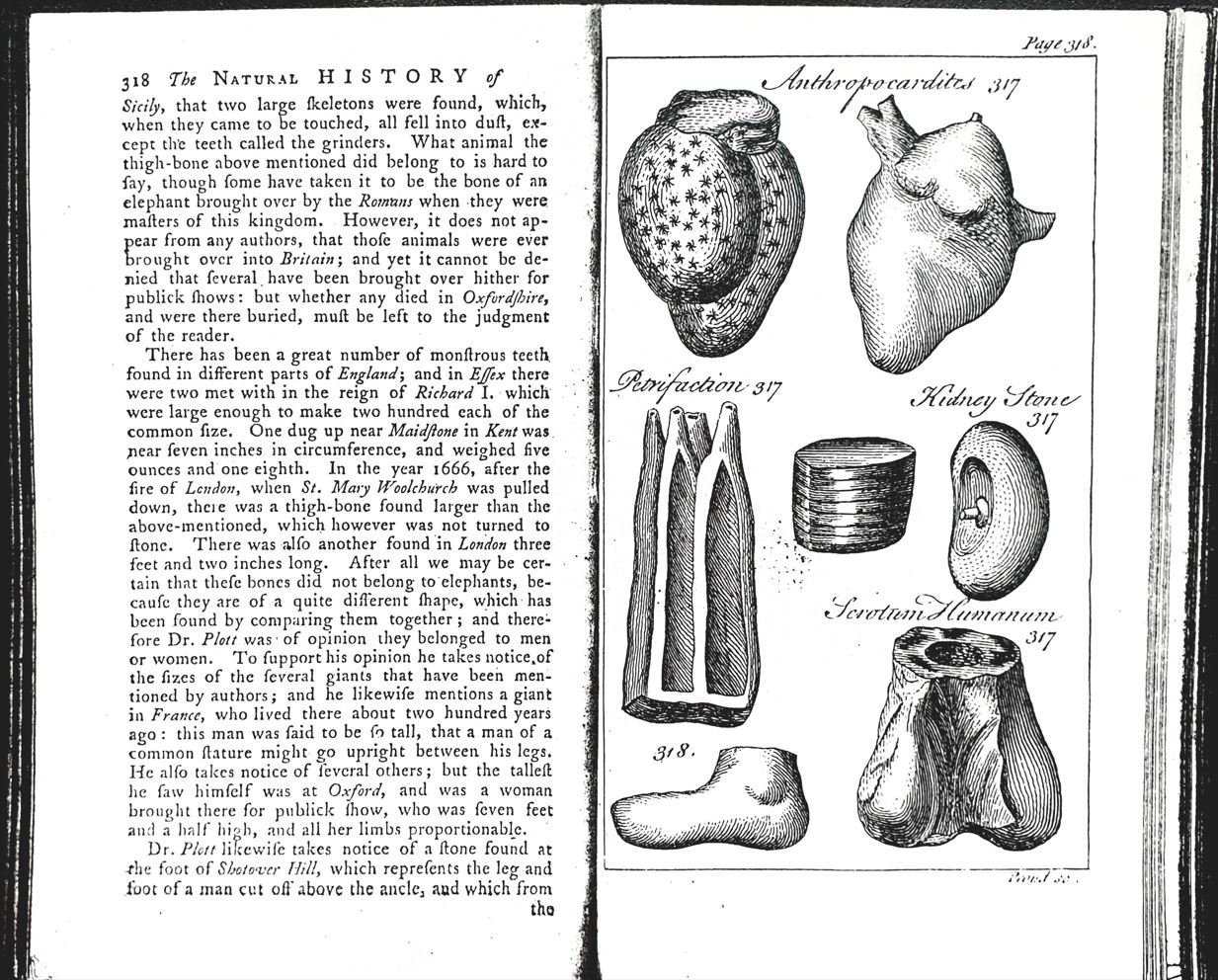

The plate featuring Scrotum humanum (not yet so named), from Plot’s Natural History of Oxford-shire

About a hundred years later, the naturalist Richard Brookes (fl. 1721–1764) described Plot’s Cornwell specimen in the fifth volume of his, A New and Accurate System of Natural History (1763), covering stones, fossils, and minerals. The purpose of this book, as its full title suggests (to which is added the Method in which Linnaeus has treated these subjects), was to use the binomial taxonomic system devised by Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778)[17] to classify the curious stones and minerals found in England.

Brookes’s description of the fossil was brief, and mostly repeated what “Dr. Plott” already said.[18] Brookes also included a drawing of the bone, which was clearly based on the one in Plot’s book, but inverted. Yet for some reason, the picture of the fossil was accompanied by the words Scrotum Humanum, presumably because someone noticed that the fossil looks like a human scrotum. It is unclear who made this connection; Brookes’s text follows Plot and states that the fossil “exactly resemble[es] the lowermost part of the thigh-bone of a man.”[19] No scrotum here. More plausible is the notion that the label was the work of the illustrator. Just before his description of the Cornwell Fossil, Brookes observes that “other stones have been found exactly representing the private parts of a man,” and the illustrations are identified only by page numbers. It is accordingly possible that the illustrator got confused about what figure went with what bit of text.[20]

Scrotum humanum as it appears in Brookes’s A New and Accurate System of Natural History

Regardless of how the misidentification happened, some later writers apparently took the idea quite seriously. French philosopher and naturalist Jean-Baptiste Robinet (1735–1820), best known for translating David Hume’s (1711–1776) Essays Moral and Political (1741), went so far as to identify musculature in each ‘testicle pouch’ and stated that the central cavity looks like a urethra in his Considerations philosophiques de la gradiation naturelle des formes (1768).[21]

It is unlikely that Robinet ever saw the fossil itself (for reasons I discuss below), yet he must have known that Plot and Brookes described it as a petrified thigh bone (he quotes both authors rigorously in different parts of the work and the illustration of the specimen is clearly copied from Brookes[22]). His reason for discounting this interpretation seems to have been his vitalistic theory of the transmutation of species, loosely based on the ideas of the 17th century Cambridge Platonists. For Robinet, everything in the universe is animated, including not only plants and animals but also rocks and minerals. These are generated from pre-existing germs in a progressive sequence of events. Everything procreates, develops, and assimilates. Fossils, then, were not once-living organisms. Rather they were organized bodies in their own right that developed from mineral germs. This meant that the Cornwell fossil in Robinet’s system could not have been a petrified bone of a once living creature. Instead it was a stoney formation sui generis, which happened to resemble the bollocks of a human male.[23]

Neither Robinet’s theory nor his interpretation were widely accepted.[24] However, they were part of a wider discussion concerning the nature of fossils—a discussion, you will recall, that was already happening when the Cornwell fossil was discovered.[25] Such discussions, as well as Robinet’s vitalistic theory, strike our current sensibilities as bizarre, yet they were very much an aspect of science at the time. It remained for later scientists to pin down the Cornwell fossil’s true nature, with John Phillips (1800–1874) concluding that it “may have been the femur of a large megalosaurus or a small ceteosaurus” (Phillips 1871).[26]

A Dinosaur by Any Other Name?

In 1970, paleontologist Beverly Halstead (1963–1991) published a paper in which he argued that because Brooke’s work was published after the 10th edition Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (considered the starting point of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature), Scrotum humanum should be considered a perfectly valid binomen and therefore name the type specimen of a new genus. This would make it the oldest generic and specific name ever applied to a (non-avian) dinosaur. Moreover, since the name Scrotum humanum was the first name given to the specimen, it has taxonomic priority over later names and thus should be considered the species’ proper scientific name.[27] This would mean that the first named dinosaur was not “Buckland’s Great Lizard,” but was a bone confused with a human ball sack.

The question of whether M. bucklandii should actually be called S. humanum went on some years. Halstead considered it irrelevant that Brookes knew that the fossil was not in fact a petrified scrotum. Still, the fact that Scrotum humanum had not been used in any literature since 1899 meant that it could be regarded, under ICZN rules, as a nomen oblatum, or “forgotten name.”[28] The Cornwell dinosaur would remain M. bucklandii. Justin Delair (1932–) and William Sarjeant (1935–2002) called this “perhaps fortunate”[29] for obvious reasons. Yet the issue was apparently serious enough that when the ICZN deleted the nomen oblatum clause in 1985 (potentially making Scrotum humanum a senior synonym of Megalosaurus bucklandii), Sarjeant made a formal application under his own (and the recently deceased Halstead’s) name to have Scrotum humanum technically suppressed so it would not usurp a more appropriate name.[30]

A recent depiction of Megalosaurus bucklandii

The ICZN subsequently concluded that the fact someone once saw a resemblance between a femur and a scrotum is a ridiculous way to name a dinosaur species. They also pointed out that the words were likely descriptive (after all, they appear alongside such rigorous taxonomic names as “Kidney Stone” and “Petrifaction”),[31] and put an end to the whole affair by declaring the name a nomen dubium (“dubious name”), thus banning it from taxonomy.[32]

There has subsequently been some discussion about whether this was the right call.[33] Nevertheless, no-one is seriously suggesting that S. humanum should be reinstated as a valid taxon. Instead, the discussions concern whether the name should be considered a nomen erratum (erroneously given name) or nomen nudum (naked name).[34] It seems that a dinosaur named after a scrotum is too good a joke for scientists to pass up, and Scrotum or Scrotum humanum is still sometimes listed as a junior synonym or nomen oblitum (reinstated into the ICZN code in 1999) of Megalosaurus.[35]

The Mystery of the Cornwell Fossil

You might be wondering what happened to the Cornwell fossil that Plot described in 1677? The answer, unfortunately, is that we don’t know; the fossil is lost and the only record we have of it are the descriptions and pictures described above.

It is not entirely clear when the Cornwell fossil went missing. It is possible that it was already lost when Brookes re-described it, as the picture is clearly copied from Plot. Thus, while I have said that the Cornwell fossil was a Megalosaurus, this is only a guess based on geological provenance and age (Middle-Jurassic, Bathhonian stage), as well as the descriptions presented in Plot’s and Brookes’s books. These descriptions are detailed enough to indicate that the fossil was probably a Megalosaurus, but the matter is not settled. (This uncertainty is another reason the ICZN considered Scrotum humanum a dubious name.) Lately, the Cornwell fossil’s identity as a Megalosaurus has been challenged, with the suggestion being that it represents another theropod, Torvosaurus, a close relative of Megalosaurus.[36]

The Cornwell fossil is not the only famous fossil to be described and then lost. The other fossils Plot describes in his book are similarly unaccounted for. Plot’s successor at the Ashmolean Museum, Edward Lhuyd (c. 1660–1709) included in his Lithophylacii Britannici Icnographia (1699) two teeth which are now thought to have belonged to a megalosaur and a sauropod, both of which are lost.[37] In fact, the whereabouts of most dinosaur fossils from the 17th and 18th century are currently unknown, preventing their restudy. (Some fossils that were thought to have been lost have since been located, but most are nowhere to be found.)[38]

Misplaced fossils are something of a theme in the history of paleontology, even after the early modern period. The enormous dorsal vertebra that E. D. Cope (1840–1897) named Amphicoelias fragilimus during his bitter rivalry with O. C. Marsh (1831–1899) has been missing since 1921 (although in this case the problem might have been disintegration rather than misplacement).[39] The fossil remains of the first discovered Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, described in 1915 by Ernst Stromer (1871–1952), stayed intact for a hundred million years only to be blown to smithereens by allied bombing raids during the 1940s.[40] But as the first described (non-avian) dinosaur bone, the Cornwell fossil might be the most famous and historically important missing fossil of all.

Title page of Dinosaur Bones by Aliki (1989). Reproduced, and given the unfortunate caption, “Little Girl and Scrotum humanum,” in Torrens (1995, 257)

So it was in late 2022, when paleontologist Darren Naish made a post on his Tetrapod Zoology blog regarding the Cornwell fossil. Naish is a well-known popularizer of everything related to dinosaurs, especially on his blog where he has argued against the ontogenetic morphing hypothesis (which holds that certain genera of dinosaurs were just different growth stages of another genus, which is related to the contention that, as Naish puts it, there were simply too many damn dinosaurs).[41] He has also publicly criticized Brian J. Ford’s theory that all dinosaurs were aquatic (yes, all of them).[42] But Naish’s report on the Cornwell fossil had a different angle, as the title announces: “Have we discovered one of vertebrate palaeontology’s most famous ‘missing’ specimens?”[43]

Naish, along with fellow zoologists Paul Stewart and Martin Simpson, had begun to suspect that the Cornwell fossil was not really lost, but that it had been hiding in plain sight, as part of the Robert Plot display in the Ashmolean Museum. The fossil in question, like the Cornwell fossil, is a distal end of a large femur, clearly belonging to a tetanuran dinosaur (the clade that includes most common therapods), maybe even a megalosaur. The main difference from the Cornwell specimen was that the hollow interior, which Plot described as containing “a shining spar-like substance” (thinking it to be petrified marrow),[44] was not visible, as a section of the shaft of the bone had been glued to the distal end. But even the crack where the two bits of bone had been joined was in the right position to fit the illustration in Plot’s work. A lot of the details of the Ashmolean specimen matched Plot’s illustration as well (when flipped as a mirror image), and even the origin of the specimen was promising, with old labels revealing it it to be from Enstone, site of a quarry within the borders of the parish of Cornwell.

The team made its first inspection of the Ashmolean specimen in 2020 (that is, they met up at the museum and stared at the Plot display), but it soon became clear that in order to achieve their goal a more hands-on approach was needed. Plot’s description of the fossil was detailed, including size and weight estimates (15 inches around the shaft, 24 inches around the distal end and weighing almost 20 pounds).[45] But to test these, the specimen would need to be examined outside the display case. Here the Collections Manager at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Hilary Ketchum, entered the picture, getting the team in contact with the right people to gain access to the specimen.

Could this be the lost Cornwell fossil, as Darren Naish, Martin Simpson, and Paul Stewart once asked? (Part of the Plot display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, 2020. Photo: Darren Naish.)

The team then reassembled in the Ashmolean to measure, weigh, and otherwise inspect the specimen and discovered… that it was not the Cornwell fossil after all. While the circumference measurements were roughly the same, the weight was too light by a half, and the team did not think it appropriate to break the shaft to see what was inside. Sadly, the mystery of the Cornwell fossil remains unsolved.[46]

But while the fossil remains at large, its significance and prominence continue to resonate. Plot’s description represents one of the first times in recorded history that humans came across evidence of something huge and ancient hiding in the rocks. This showed that there were literal giants beneath our feet, and that the world of today is unlike the earth of the past. Scientists in Plot’s time were perplexed by these discoveries, struggling to come up with adequate explanations, but it was the beginning of something, and beginnings hold a special fascination for limited beings such as ourselves.[47]

The whole Scrotum Humanum issue might have been, as Naish described it, “a silly waste of time”[48] and Halstead’s attempted taxonomic revision an elaborate joke. Still, it reveals something about how we approach the thought of a world that does not exist anymore. Plot and his contemporaries saw the bones as the remains of mythical giants because they expected to find traces of such giants inhabiting the earth. The scientific paradigm shift of the early 1800’s, driven by people like Cuvier, Buckland, Owen, and Mantell, was enormous, and it is difficult to appreciate it in all its aspects. Even today, new dinosaur discoveries continue to spark interest and wonder. One can scarcely imagine how people back then experienced the revelation that the earth had once been populated by strange reptilian giants. Here poetry, like Joseph Victor von Scheffel’s (1826–1886) “Der Ichtyosaurus,” may help our limping imaginations:

The rushes are strangely rustling,

The ocean uncannily gleams,

As with tears in his eyes down gushing,

An Ichthyosaurus swims.

The Plesiosaurus, the elder,

Goes roaring about on a spree;

The Plerodactylus even

Comes flying as drunk as can be.

The end of the world is coming,

Things can't go on long in this way;

The Lias formation can't stand it,

Is all that I've got to say!

And this petrifideal ditty?

Who was it this song did write?

Twas found as a fossil album leaf

Upon a coprolite.

Henry De la Beche’s watercolor, titled Duria Antiquior, a more ancient Dorset. This is often thought to be the first reconstruction of past life in its natural environment based on fossil evidence

References

Bakker, Robert T. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction. Zebra Books.

Brookes, Richard. 1763. A New and Accurate System of Natural History vol. 5, The Natural History of Waters, Earths, Stones, Fossils, and Minerals with their Virtues, Properties, and Newbery.

Buckland, William. 1824. “Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield.” Transactions of the Geological Society of London 1(2):390–396.

Buffetaut, Éric. 1979. “A propos du reste de dinosaurien le plus anciennement décritl’interprétation de J. B. Robinet (1768).” Histoire et Nature 14:79-84.

Carpenter, Kenneth. 2006. “Biggest of the Big: A Critical Re-evaluation of the Mega-Sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus Cope, 1878” in Foster, John R. & Lucas, S. G. (eds) Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36, 131–137.

Carpenter, Kenneth. 2018. “Maraapunisaurus fragillimus, n.g. (formerly Amphicoeliasfragillimus), a basal rebbachisaurid from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Colorado” Geology of the Intermountain West 5:227–244.

Collini, Cosimo A. 1784. “Sur quelques Zoolithes du Cabinet d'Histoire naturelle de S. A. S. E. Palatine & de Bavière, à Mannheim.” Acta Theodoro-Palatinae Mannheim 5:58–103.

Delair, Justin B. & Sarjeant, William A. S. 1975. “The Earliest Discoveries of Dinosaurs.” Isis 66(1):4–25.

Delair, Justin B. & Sarjeant, William A. S. 2002. The Earliest Discoveries of Dinosaurs: the Records Re-examined.” Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 113:185–197.

Dean, Dennis R. 1999. “Foreword” in Dean, Dennis R. (ed) The First “Dinosaur” Book. Scholar’s Facsimiles & Reprints, 11–15.

Ford, Brian J. 2018. Too Big to Walk: The New Science of Dinosaurs. HarperCollins.

Forsman, Jan. 2015. “Brontosauruksen yö (Night of the Brontosaurus).” niin & näin 85 (online extra). URL=http://www.netn.fi/artikkeli/brontosauruksen-yo English translation: URL= https://www.academia.edu/16608941/Night_of_the_Brontosaurus

Halstead, Lambert B. 1970. “Scrotum humanum Brookes, 1763 — the first named dinosaur.” Journal of Insignificant Research 5(7):14-15.

Halstead, Lamber B. & Sarjeant, William A. S. 1993. “Scrotum humanum Brookes – the earliest name for a dinosaur.” Modern Geology 18:221-224.

Herodotos (Hdt). 2013 The Histories. Translation by Holland, Tom. Penguin Classics.

Larson, Neal L. 2008. “One hundred years of Tyrannosaurus rex: the skeletons” in Larson, Peter & Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.) Tyrannosaurus rex, The Tyrant King. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1–55.

Mantell, Gideon. 1827. Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex, containing a general view of the geological relations of the south-eastern part of England, with figures and descriptions of the Fossils of Tilgate Forest. Lupton Relfe.

Mayor, Adrienne. 2000. The First Fossil Hunters. Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times. Princeton University.

McGowan, Christopher. 2001. The Dragon Seekers: How and Extraordinary Circle of Fossilists Discovered the Dinosaurs and Paved the Way for Darwin. Perseus Publishing.

Molnar, Ralph E.; Kurzanov, Seriozha M. & Dong Zhiming. 1990. “Carnosauria” in Weishampel David B.; Dodson, Peter & Osmólska, Halzska. (eds.) The Dinosauria. University of California Press, 169–209.

Naish, Darren. 2012. “Palaeontology bites back…” Laboratory News May 2012:31–32.

Naish, Darren. 2018. “A Vast Quantity of Evidence Confirms That Non-Bird Dinosaurs Were Not Aquatic – Supplamentary Information” New Lands: Were Dinosaurs too big? Conway Hall, 15th May 2018.

Norman, D. B. 1992. “Dinosaurs Past and Present.” Journal of Zoology 228:173–181.

Osborn, Henry F. 1905. “Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs.” Bulletin of the AMNH. 21(14):259–265.

Osborn, Henry F. 1916. "Skeletal adaptations of Ornitholestes, Struthiomimus, Tyrannosaurus” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 35(43):733–771.

Osborn, Henry H. & Mook, Charles C. 1921. “Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias, and other Sauropods of Cope.” Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, New Series 3(3):249–387.

Owen, Richard. 1842. “Report on British Fossil Reptiles, Part II” in Dean, Dennis R. (ed) 1999. The First “Dinosaur” Book. Scholar’s Facsimiles & Reprints.

Osi, A., Prondvai, E., & Géczy, B. 2010. “The history of Late Jurassic pterosaurs housed in Hungarian collections and the revision of the holotype of Pterodactylus micronyx Meyer 1856 (a ‘Pester Exemplar’).” Geological Society 343(1):277–286.

Parkinson, James. 1822. Outlines of Oryctology: An Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains. London.

Paul, Gregory S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon and Schuster.

Paul, Gregory S. 2019. “Determining the Largest Known Land Animal: A Critical Comparison of Differing Methods for Restoring the Volume and Mass of Extinct Animals” Annals of Carnegie Museum 85(4):335–358.

Pausanias. (Paus.) 1900. Description of Greece vol. I. Translation by Shilleto, Arthur Richard. George Bell & Sons.

Phillips, John. 1871. Geology of Oxford and the Valley of Thames. Clarendon Press.

Plot, Robert. 1677. The Natural History of Oxfordshire, Being an Essay Toward the Natural History of England. Theater and S. Millers.

Prothero, Donald R. 2019. The Story of the Dinosaurs in 25 Discoveries: Amazing Fossils and the People Who Found Them. Columbia University Press.

Robinet, Jean-Baptiste. 1766. De la Nature, Tome Quatrieme. Harrevelt.

Robinet, Jean-Baptiste. 1768. Considerations philosophiques de la gradation naturelle des formes de l’etre ou les Essais de la Nature qui apprend a faire l’homme. Charles Saillaint.

Rieppel, Olivier. 2022. "The first ever described dinosaur bone fragment in Robinet's philosophy of nature (1768)." Historical Biology 34(5):940–946.

Spalding, David A. E. & Sarjeant, William A. S. 2012. “Dinosaurs: The Earliest Discoveries” in Brett-Surman, M. K.; Holtz jr. Thomas R. & Harlow, James O. (eds) The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press, 3–24.

Taquet, Philippe & Padian, Kevin. 2004. “The earliest known restoration of pterosaur and the philosophical origins of Cuvier’s Ossemens Fossiles.” Comptes Rendus Palevol 3(2):157–175.

Torrens, H. S. 1995. “The dinosaurs and dinomania over 150 years” in Sarjeant, William A.S. (ed) Vertebrate Fossils and the Evolution of Scientific Concepts. Gordon and Breach Publishers, 255–284.

Woodroff, D. Carey & Foster, John R. 2014. “The fragile legacy of Amphicoelias fragillimus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda; Morrison Formation – latest Jurassic).” Volumina Jurassica 12(2):211–220.

Footnotes

[1] See e.g., Charles Choi, “The Brontosaurus Is Back”, Scientific American, 7/iv/2015. Also Forsman (2015).

[2] https://nhmu.utah.edu/articles/2023/05/how-we-came-see-dinosaurs-color

[3] https://news.mit.edu/2020/study-timing-dinosaurs-evolution-0729

[4] Buckland (1824, 390, 392). Buckland gives partial credit for the name to William Conybeare (1787–1857). The name Megalosaurus was first suggested by James Parkinson (1755–1824). Parkinson (1822, 298). Cf. Paul (1988, 281).

[5] Even flying pterosaurs, of which remains had been found since late 1700’s, were originally considered to be marine animals due it being considered more likely for unknown species to live in the ocean depths. See Collini (1784). Cf. Taquet & Padian (2004); Osi, Prondavai & Géczy (2010).

[6] McGowan (2001, 88). At the time, the predominant scientific view was that animals do not go extinct as it would be against the great chain of being, in which all created beings are in perfect harmony. Extinction would cause missing links in that chain and be against the natural order. Cuvier was one of the earliest supporters of extinction theory but was met with opposition throughout his life. One of his opponents was Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) who thought that instead of going extinct, species evolve into other species over time, which Cuvier opposed. Darwin’s theory of natural selection then explained that extinction and evolution could be mutually inclusive.

[7] Ibid, 9. Anning was excluded outside of the academic research of her time due to her gender, even though she was typically more deeply acquainted with the fossil findings she had made than the academics who published research papers on them, often without even mentioning her name. See ibid, 11–27.

[8] Ibid, 10. Even though he spent most of his research life among fossilized remains, Buckland himself was not one. He is described as a lively and entertaining lecturer, suddenly dashing towards his students waving a hyena skull and shouting “What rules the world?” (The answer Buckland was expecting was “the stomach, sir”.) Ibid, 29.

[9] Mantell (1827, 67).

[10] Paus. 5.13; Hdt. 1.68. See Mayor (2000, chapter 3).

[11] See McGowan (2001, 1); Prothero (2019, 3); for a detailed look at early fossils, see Spalding and Sarjeant (2012).

[12] Ashmolean is the oldest public museum in the world, established in 1677 in Oxford to house items donated for the university by Elias Ashmole, including the stuffed body of the last dodo seen in Europe. Currently, the dodo, as well as the remains that Buckland named Megalosaurus, are exhibited at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. It seems that gaining sufficient funding in academia was just as difficult in the 1600s as it is today, and it is possible that Plot worked simultaneously as a professor and as a curator as the payment from each was not enough to support him.

[13] Plot (1677, 132).

[14] Ibid, 133.

[15] Ibid, 133–136.

[16] Ibid, 138.

[17] Although a system close to what is now known as bionomial nomenclature was already developed by Swiss brothers Johann (1541–1613) and Gaspard (1560–1624) Bauhin for botanical work around a century earlier, Linnaeus was the first to systematically use a binomial taxonomy in his book Systema Naturae (1st ed. 1736, 10th ed. 1758). For this, Linnaeus is still known as the “father of modern taxonomy.”

[18] Brookes (1763, 317–318). As an interesting side note, while the Cornwell fossil seems to have been the first dinosaur discovery to be described, it was not the first enormous fossil discovered in England. Plot refers to two large teeth found in Essex during the reign of Richard I (1157–1199), and lists several other outsized bones and teeth found in various parts of England (Plot 1677, 134–135). One such discovery was made in 1666 in London, when upon pulling down the St. Mary Woolchurch, which had been damaged in the Great Fire of London, a thigh-bone “much bigger and longer than ours of stone could in proportion be, had it been entire” was found (ibid, 135; cf. Brookes 1763, 318). Plot took this as more evidence that these were human remains since “how Elephants should come to be buried in Churches is a question not easily answered, except we will run to so groundless a shift, as to say, that possibly the Elephants might be there buried before Christianity flourished in Britan and that these Churches were afterward casually built over them” (Plot 1677, 315). Plot is obviously mocking, yet he was closer to the truth than he even realized. See also Sam Kriss, “Jurassic Lark”, First Things, iii/2023.

[19] Brookes (1763, 317).

[20] Ibid. See Rieppel (2022, 941). Norman (1992, 173–174) calls it an “editorial error”.

[21] Robinet (1768, 31). See also Buffetaut (1979) and Rieppel (2022).

[22] Ibid. 19–20, Pl. 1, fig. 1. See Buffetaut (1979, 82).

[23] Robinet (1766), 209–210; 1768, 31. See Rieppel (2022, 942, 945).

[24] Though despite Delair and Sarjeant’s (2002, 186) claim, Robinet did not consider the fossil to actually be a scrotum.

[25] See esp. Rieppel (2022, 944).

[26] Phillips (1871, 164). Cf. Delair & Sarjeant (1975, 8); Rieppel (2022, 941).

[27] Halstead (1970)

[28] Ibid.

[29] Delair & Sarjeant (1975, 8).

[30] Halstead & Sarjeant (1993).

[31] Brookes (1763, 318).

[32] Halstead & Sarjeant (1993). See also Delair & Sarjeant (2002); Spalding & Sarjeant (2012, 10); Prothero (2019, 6–7).

[33] See e.g., Molnar, Kurnzanov & Dong (1990, 192) who list Scrotum humanum as a dubious yet distinct carnosaur.

[34] Rieppel (2022, 945); Mortimer, Mickey, “‘Scrotum humanum’ a torvosaur and Jurassic Chinese theropod updates”, The Theropod Database, 9/i/2023.

[35] See e.g., Paul (1988, 280–281). For more on taxonomic priority relating to the infamous Brontosaurus vs. Apatosaurus case, see Forsman (2015). Scientific rigidity almost came to bite paleontologists on the backside when in 2000 it was confirmed that Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the most recognized and beloved dinosaur species, had already been named Manospondylus gigas by Cope in 1892, a full thirteen years before Cope named it the “King Tyrant Lizard.” See Larson (2008, 37–38, 50); Prothero (2019, 224). Cf. Osborn (1905); (1916). Instead of following priority, most referred to the changed ICZN ruling from 1st of January 2000, stating that a name that has been considered valid for 50 years cannot be replaced by a name that has been considered invalid during the same time, and quickly changed the subject. Mike Taylor, “So why hasn’t Tyrannosaurus been renamed Manospondylus”, Miketaylor.org, 27/viii/2002; Matt Martyniuk, “What is a Nomen Oblitum? Not What You Probably Think”, DinoGoss, 5/ix/2010. At the time of writing, no-one appears to have made an official application for protecting the T. rex name and the case seems to have been shoved under a rug.

[36] Delair & Serjeant (1975, 8); Rieppel (2022, 941); Mortimer (2023). The fossil cannot be the type species T. tanneri as it is from the later Callovian stage of the Jurassic. Megalosaurus and its clade Megalosauridae have though been treated as kind of a “wastebasket” for partial descriptions and unidentified mid-size theropod dinosaur discoveries. As such Megalosaurus has at one point or another included hundreds of sub-species from five different continents, spanning 100 million years, with several of these sub-species been granted their own genus (including Carcharodontosaurus and Dilophosaurus). See Paul (1988, 281–282); Prothero (2019, 13).

[37] Llhuyd 1699, pl. 16. Reproduced in Delair & Sarjeant 2002, 186–187. Cf. Delair & Sarjeant 1975, 8.

[38] For a catalogue of these early fossils, pre-dating Buckland’s Megalosaurus specimen, see Delair & Sarjeant 1975, 8–12; 2002, 186–192. Cf. Spalding & Sarjeant 2012, 11–13; Prothero 2019, 5.

[39] See Osborn & Mook 1921, 279; Carpenter 2006, 134; Woodroff & Foster 2014. See also Forsman 2015. Due to the fossil material being lost, most of Cope’s size estimates, which would have placed Amphicoelias the largest vertebrate that has ever existed, have been discarded as exaggerations. In 2018, A. fragillimus was renamed Maraapunisaurus fragillimus due to taxonomic relocation (Carpenter 2018), rekindling new size estimates placing it again among the largest known sauropods. See Paul (2019).

[40] Prothero (2019, 207–208).

[41] “Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs”, TetZoo 17/iv/2020. Cf. Prothero (2019, 109–111).

[42] See Naish (2012); (2018). Cf. Ford, “A prehistoric revolution”, Laboratory News, 3/iv/2012; 2018. My favorite part of Naish’s answer is the following: "Ford specifically stated that the tails of large dinosaurs were too heavy to permit terrestrial life. However, geometrical modelling performed by dinosaur specialists and utilising techniques somewhat more rigorous than Ford's technique of dunking toy dinosaurs in water most definitely does not find even the most substantial, most muscular dinosaurian tail to present any problem as goes terrestrial locomotion” (Naish 2012, 32).

[43] “Robert Plot’s Lost Dinosaur Bone”, TetZoo, 16/xii/2022.

[44] Plot (1677, 131).

[45] Ibid, 131–132.

[46] “Robert Plot’s Lost Dinosaur Bone”, TetZoo, 16/xii/2022.

[47] The Cornwell fossil is not the only example here: a giant neogenic salamander Andrias scheuchzeri was originally described as Homo diluvia testis (“Human who witnessed the Flood”) by Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672–1733) in 1726. See Prothero (2019, 4). Interestingly, no-one seems to have argued for the priority of the name, or claimed that a certain Pleistocene mammal should be renamed Orestes.

[48] “Robert Plot’s Lost Dinosaur Bone”, TetZoo, 16/xii/2022.