* This is Part 1 of a two-part installment of “Problematica.” It is about the problem of explaining novel structures in late nineteenth century evolutionary science. I will place the link to Part 2 here when it is available. Problematica is written by Max Dresow…

In an 1886 book, Evolution of To-day, the bacteriologist Herbert Conn remarked that “Natural selection, or Darwinism, is… almost everywhere acknowledged as insufficient to meet the facts of nature, since many features of life are not explained by it” (243). Twenty years later, the entomologist Vernon Kellogg began his survey, Darwinism To-day, with a similarly frank appraisal. “The fair truth is that the Darwinian selection theories, considered with regard to their claimed capacity to be an independently sufficient mechanical explanation of descent, stand to-day seriously discredited in the biological world” (Kellogg 1907, 5). Like Conn, Kellogg harbored no animus toward Darwinism, and was happy to admit that selection must act whenever variations favorable or injurious to an organism happen to arise. Still, neither man believed that selection provided a satisfactory account of descent, including an answer to what Kellogg deemed the “basic problem” of evolution: the problem of beginnings (Kellogg 1907, 35). To explain the origin of novel structures, something beyond the selection of “fluctuating” variation was needed. But what this was remained a matter of warm contention during the fifty or so years following Darwin’s death (1882–).

Herbert Conn (1859–1917), left, and Vernon Kellogg (1867–1937), right

Paleontologists were particularly impressed by the problem of beginnings. Edward Drinker Cope titled a essay collection The Origin of the Fittest, implying that while selection may explain the survival of the fittest, it doesn’t explain how the “fit” came to be there in the first place. Henry Fairfield Osborn reached a similar conclusion after observing that characters tend to appear in phyletic lineages well before they could serve any conceivable purpose. (His examples included mammalian molar cusps and titanothere horns.) From this he concluded that “variations follow definite lines from their incipient stages,” and— relatedly— that the results of the new genetics could have no bearing on the origin of characters (Osborn 1891, 205). However, in doubting the power of selection to fashion novel characters, Osborn locked arms with leading geneticists like William Bateson, Reginald Punnett, and Thomas Hunt Morgan.*

[* This must have been one of the few things Osborn and Morgan agreed upon (Rainger 1991). Anyway, it illustrates the extent to which skepticism about the power of selection bridged the divide separating museum naturalist-types and the laboratory scientists who had seized the initiative in biological research.]

I have been interested in the problem of beginnings for a long time. I even wrote a chapter of my master’s dissertation on the subject way back in 2015. What struck me then— and continues to strike me now— was how ubiquitous the problem was in the decades following Darwin's death: not just among paleontologists, but among experimental biologists too. It would be an exaggeration to call it the leading problem of the period, since the related problem of the nature of variation was just as important. (And as Peter Bowler (1996) has pointed out, most evolutionists of the time were involved in the orthogonal project of tracing out genealogical lineages and reconstructing hypothetical ancestors.) Still, the problem of beginnings was everywhere in the late nineteenth century, and constituted an important check on the ambitions of more assertive forms of (neo-) Darwinian theory.

It is still with us. Or perhaps it would be accurate to say that, after a period in which it receded from prominence, novelty is back on the agenda. Evolutionary developmental biology is what brought it back. Beginning in the 1980s, “evo-devo” biologists declared evolutionary novelty “the core of their identity as a research program” (Love 2005, 1). Some revived talking points from Conn and Kellogg. One even titled a book The Making of the Fittest in what I would like to think was a nod to Cope, but was probably just a coincidence (Carroll 2006). Anyway, the thought was the same. Selection selects, but it can only select from the materials presented to it by development. For both Cope and the evo-devoists this provided a rationale for a research program dedicated to understanding how the objects of selection came to exist in the first place.

An image from a 1997 publication, “Regulation of number and size of digits by posterior Hox genes: a dose-dependent mechanism with potential evolutionary implications.” This image shows dose-dependent variation of digit patterning in mouse feet: an observation that may help account for the evolutionary origin of distal limb structures in mice

It is interesting that evo-devo biologists have revived talking points from an earlier period in the history of evolutionary science. But my focus in this essay is on that earlier period. Specifically, I am interested in the arguments marshaled in support of the claim that selection cannot explain the origin of novel features. Three such arguments enjoyed wide circulation in the decades following Darwin’s death. I will discuss each of them, but will pay a special attention to what I term “Mivart’s Dilemma,” or the inability of selection to explain the incipient stages of novel structures.* For a while the argument seemed to be decisive. William Bateson referred to it as “by far the most serious” difficulty facing the theory of natural selection (Bateson 1894, 16). T.H. Morgan called it “a veritable stumbling block [for Darwin’s] theory” (Morgan 1903, 135). Conn judged it to be “one of the most serious difficulties in the way of accepting natural selection as a satisfactory solution of descent” (Conn 1900, 134). And R.S. Lull— professor of a young George Gaylord Simpson— ascribed the entire body of orthogenetic theory to “the difficulty of explaining the beginnings of… new organs by the selection of individual variations” (Lull 1920, 175). A dragon indeed.

[* Mivart was St. George Jackson Mivart (1827–1900)— more on him in a moment.]

But where did Mivart's Dilemma come from, and how was it distinguished from other anti-selectionist arguments circulating at the time? These are the questions for the first part of this essay. Then, in Part 2, I will explore how scientists responded to Mivart’s Dilemma in the decades following Darwin's death. I will do this by examining two general treatments of evolutionary theory— Conn’s The Method of Evolution (1900) and Kellogg’s Darwinism To-day (1907)— and two empirical research programs— those of William Bateson and Theodor Eimer. But first things first. Who names a kid St. George, and why did the kid spend so much energy criticizing natural selection?

Meet St. George Mivart

This essay doesn't have a protagonist, but it does have a central figure— the Darwinian excommunicate St. George Mivart . While not a household name like his mentor, T. H. Huxley, Mivart was an important person in Victorian England: a credentialed anatomist and the author of many popular works bridging science and Catholic theology. Today he is best remembered as the person who first assembled a series of objections to the selection theory “that would later be exploited during the eclipse of Darwinism” (Bowler 1983, 22–23). These gained wide circulation with the publication of his first book, On the Genesis of Species (1871), in particular, his eponymous dilemma.

St. George Mivart in midlife

“The life of St. George Mivart fits the Victorian era,” his biographer writes. “In all his life, in the work he did and in the controversies in which he engaged, he reflected the conflicting currents of thought and feeling which marked the age” (Gruber 1960, 2). Mivart was born on November 30, 1827, to wealthy parents in London. His father James was a respected socialite and proprietor of Mivart’s Hotel on Brook Street (today, Claridge’s). This more or less permanently freed St. George from the need to make the living. He would go on to pursue the career of a gentleman scientist, rubbing elbows with some of the biggest scientific stars of the age (most notably, Huxley and his arch-nemesis, Richard Owen).

Mivart’s life took a sharp turn in 1844, when, at the age of sixteen, he entered St. Chad’s Cathedral in Durham and became a Roman Catholic. Following his conversion, he took up the cudgels in defense of the faith, often clashing loudly with his opponents. Mivart would go on to become one of the most influential lay Catholics in Great Britain. Yet he remained forever a freethinker, and ended his life an apostate, casting vitriolic aspersions on the throne of Saint Peter (Root 1985). It seems, in hindsight, an inevitable conclusion to a tempestuous life. Mivart’s piety was sincere, and supplied a main theme of his voluminous public writing. But his gestures at orthodoxy concealed a rebelliousness that lay near the heart of his many excursions in science and philosophy. In Gruber’s words: “What is surprising is not that Mivart ended his life as a heretic, but that the always uneasy alliance between him and the Church should have lasted so long” (Gruber 1960, 144). His uneasy alliance with the Darwinians was not so resilient, as I will explore below.

Professionally, Mivart was a comparative anatomist specializing in the osteology of primates (Bigoni and Barsanti 2011). His work was widely respected, particularly before the eclipse of osteology in late nineteenth century comparative anatomy, and Darwin discussed it in The Descent of Man. In addition, Mivart was an early advocate of the “lateral fold” hypothesis concerning the origin of paired fins, upholding it against the authority of Carl Gegenbaur and his school. He died in London in 1900.

Mr. Darwin’s Critics: Three Criticisms of Natural Selection

Back to the main business of this essay.

Our first task is to distinguish three arguments marshaled in support of the claim that selection is unable to originate novel features. This is the more difficult because the arguments were often presented side by side in the period following Darwin’s death. Still, it is useful to distinguish them, not least because different arguments made different kinds of mischief for the selection theory. I will call them Nägeli’s Argument, Jenkin’s Argument, and Mivart's Dilemma, respectively, and my perhaps somewhat controversial claim is that Mivart's Dilemma played the most decisive role in structuring attitudes towards natural selection during the decades following Darwin’s death. But that's an argument for Part 2. First we need to look at the arguments themselves.

Nägeli’s Argument, or the negativity of selection

The idea that selection is a wholly negative force is almost as old as Darwinism itself (Gould 2002). Selection is impotent in creation (the thought goes)— it can only preserve or destroy. This means that it can play no role in origins since it is unable to produce the materials it acts on. Selection, in the view of Dutch botanist Hugh de Vries, is a “wholly a restraining and cutting-back factor, not at all a formative one” (Kellogg 1907, 333). Similarly, British geneticist R. C. Punnett wrote that “the function of natural selection is selection and not creation… It merely decides whether [a variety] is to survive or to be eliminated” (Punnett 1911, 175). Swiss botanist Carl Nägeli compared natural selection to a gardener who prunes the tree of life while producing no new growth (Nägeli 1865). Charles Lyell compared it to two members of “the Hindoo Triad,” the preserver Vishnu and the destroyer Siva, and remarked that it lacked the creator Brahma. Finally, here is William Bateson, writing in a volume celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Origin of Species:

We must relegate Selection to its proper place. Selection permits the viable to continue and decides that the nonviable should perish…[As] the course of descent branches in successive generations, Selection determines along with branch Evolution should proceed, but it does not decide what novelties that branch shall bring forth. (Bateson 1909, 96)

Statements like these could be multiplied ad nauseum, but they all hum the same tune. “Natural selection” is the name we give to those factors that preserve the fit and eliminate the unfit in the struggle for life. But evolution “means producing more new things, not more of what already exists” (Morgan 1916, 154, emphasis added). It follows that natural selection cannot be a complete explanation of evolution, because it is no explanation at all of the origin of characters.

A common way of describing the (entirely negative) action of selection was by analogy with a sieve. This was thought by many to provide a better understanding of how selection works than the original metaphor: the human breeder selecting variants

As Gould (2002) observed, what I’m calling “Nägeli’s Argument” was the single most widespread criticism of natural selection during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was entirely a priori, but was evidently no less persuasive for this, to judge by its prevalence in the writings of clever scientists. This might be taken to indicate that Nägeli’s Argument was the most important anti-Darwinian argument in the decades following Darwin’s publication. Yet I suspect that much of its persuasiveness owed to other arguments that were frequently marshaled alongside it. After all, there is an obvious rejoinder to Nägeli’s Argument in its bare form. Darwin never claimed that natural selection directly originates novel features— only that it scrupulously preserves advantageous features when they chance to appear. Yet natural selection can still be regarded as “creative” insofar as it directs evolutionary change and shapes novel features from the material supplied by haphazard variation (see Beatty 2016). To really defang selection, what was required was (1) a demonstration that this variation has limits (confining the operation of selection to a tightly circumscribed space) or (2) a demonstration that selection cannot get new features “off the ground” without outside assistance. That is what the next two arguments attempted to provide, and it is these arguments (particularly the latter) that convinced a large number of biologists that selection is impotent in creation.

Jenkin’s Argument, or the intrinsic limits to variation

According to many accounts, the theory of natural selection received its heaviest blow from the hand of H. Fleeming Jenkin, a celebrated polymath and intimate of William Thomson (Lord Kelvin). Darwin himself ranked Jenkin’s review as the most useful criticism he ever received, and commenters have agreed in awarding it pride of place among the early attacks on the Origin. It began with the allegation that evidence from domestic productions speaks against the idea that nature has “the power indefinitely to magnify the peculiarities which distinguish [her] breeds from the original stock” (Jenkin 1867, 278–279). While selection might “improve hares as hares, and weasels as weasels”— bringing useful faculties to a higher degree of development and doing away with harmful vestiges— it is powerless to create new organs and new species. The reason, Jenkin thought, is the existence of factors intrinsic to the organization of each being that confine variation within certain limits:

A given animal or plant appears to be contained, as it were, within a sphere of variation: one individual lies near one portion of the surface, another individual, of the same species, near another part of the surface; the average animal at the centre. (Jenkin 1867, 282)

Jenkin proceeded to argue that while an outbreeding organism “may produce descendants varying in any direction, [it] is more likely to produce descendants varying towards the centre of the sphere [than its periphery]” (the phenomenon of reversion). As a consequence, outbreeding tends to counteract deviations from the norm, resulting in a backsliding of offspring towards the average character of the race. The effect will tend to be strongest for individuals closest to the periphery of the sphere, rendering the gradual evolution of new “organs or habits,” leading to the appearance of new species, impossible. Unless by a sudden leap, limits on variation will prevent natural processes from breaching the boundary of the sphere. But evolution by leaps is not Darwinism, and in fact differs little from “what might be termed creation [in that it involves the appearance, all at once, of true-breeding types]” (290). It follows that natural selection is impotent in creation, and is limited to improving existing designs within the constraints imposed by intrinsic limits on variability.

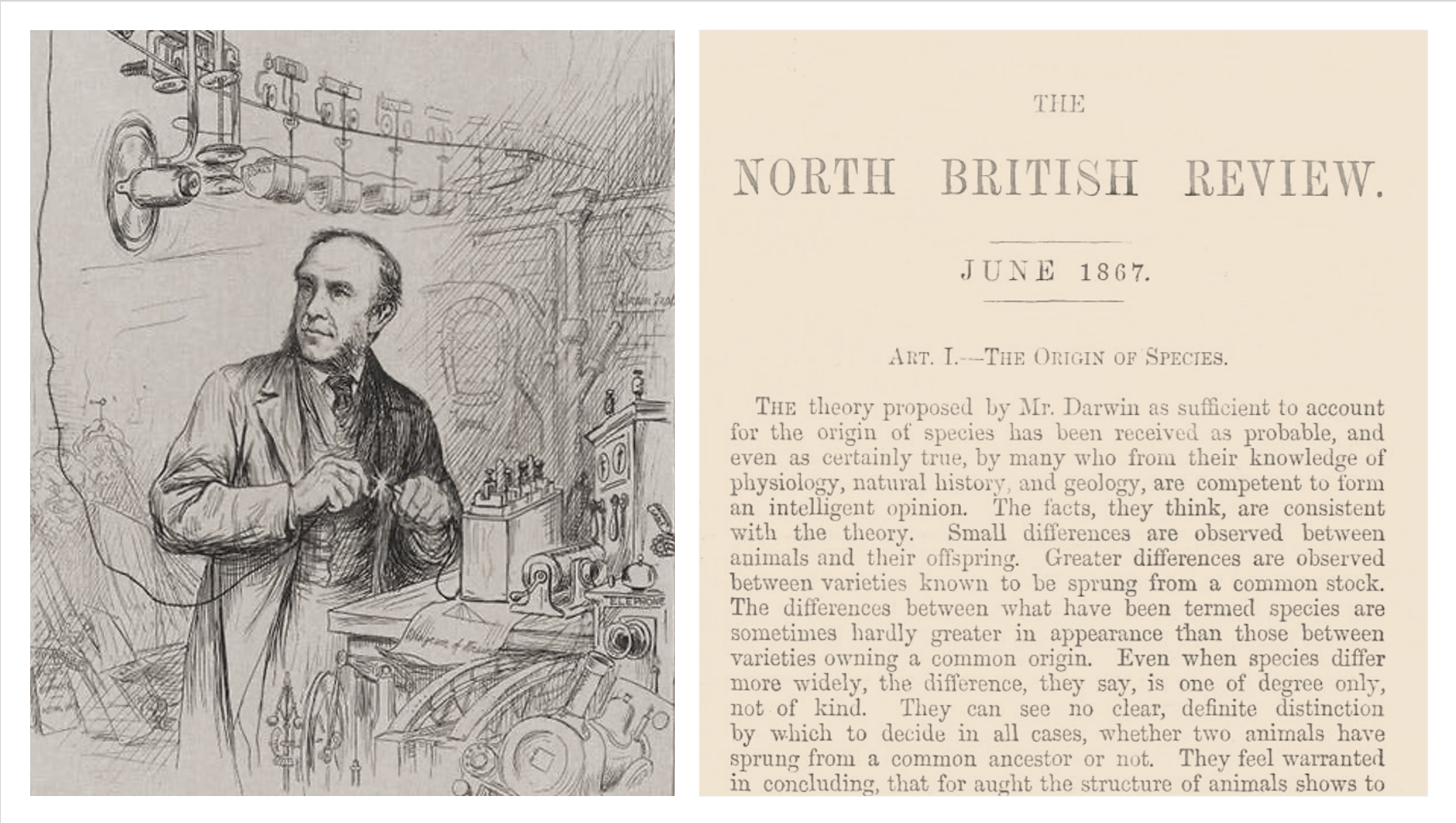

Left: Fleeming (pronounced “Fleming”) Jenkin in his electrical workshop, looking every bit the mad inventor. Right: Jenkin’s famous review of the Origin in the North British Review (1867)

In calling this line of reasoning “Jenkin’s Argument,” I am simplifying somewhat. Jenkin gave a number of arguments in his review, the most well-known of which concerns the swamping of “single variations” (Darwin’s term for unusual, discontinuous changes) by interbreeding. This “swamping argument” has traditionally been regarded as the fulcrum of Jenkin’s critique, and as occasioning Darwin’s remark (in a letter to Hooker) that “Fleming Jenkyns [review] has given me much trouble.” Yet as several historians have observed, the swamping argument was of relatively little consequence to Darwin, since he never thought much of single variations as inputs to adaptive evolution anyway (Vorzimmer 1970; Gould 1991; Morris 1994). Jenkin’s remarks about variational limits were more relevant to Darwin’s preferred method of evolution: the accumulation of “individual differences” within lines of descent. It also added to Darwin's growing problem with evolutionary novelty, since it implied that while selection may “fiddle in minor ways with parts already present,” it “cannot construct anything new” (Gould 1991, 347). In Jenkin’s words: “When we have granted that the ‘struggle for life’ might produce the pouter or the fantail, or any divergence man can produce, we need not feel one whit the more disposed to grant that it can produce divergences beyond man’s power” (Jenkin 1867, 280). Selection may be the cause of local improvement, but it is not an explanation of real evolutionary novelty.

Darwin made some small modifications to the Origin to deal with Jenkin’s arguments, but was ultimately little moved by them (Hoquet 2024). Still, the problem of novelty was becoming a thorn in his paw, and in 1872, he added a new chapter to the Origin in the hopes of settling the issue. His main interlocutor in this chapter was not the engineer Jenkin, however— it was the zoologist Mivart, author of arguably the most influential objection to the selection theory formulated in Darwin’s lifetime.

Mivart’s Dilemma, or the inutility of incipient structures

Jenkin’s essay appeared in the North British Review in June of 1867. Two years later, an article appeared in the Catholic periodical The Month entitled “Difficulties of the Theory of Natural Selection” (1869). Like Jenkin’s review, its authorship was undisclosed (although it was obvious to many who had written it). Consisting of three parts, the article was Mivart’s first in a series of attacks on the selection theory, and commenced with a laundry list of criticisms. The most famous of these was the “incompetency of Natural Selection to account for the incipient stages of useful structures,” as he called it in his 1871 book, On the Genesis of Species:

What we have now to bring forward may be summed up as follows… That though potent to explain the maintenance of further extension of favourable variations, the theory [of natural selection] fails to account for the conservation and development of the first beginnings of such. (Mivart 1869, 41)

More concretely, Mivart doubted that natural selection could originate features like mimicry in butterflies, limbs in vertebrates, and whalebone (baleen) in whales. The reason was that the first beginnings of such features would confer no advantages on their possessors— what good is a smidgen of baleen, after all? Or “the first faint beginnings” of resemblance to a toxic butterfly (Mivart 1871, 41)? Time and again, Mivart implied that only an internal mechanism (“an innate force and tendency [to change]”) can generate real novelty, bypassing the dilemma of incipient structures (Mivart 1871, 264). Yet as Mivart correctly noted, such processes were thoroughly un-Darwinian:

The theory of “Natural Selection” excludes the notion of a sudden resemblance [of, e.g., an insect] to a leaf or a bamboo. Any spontaneous tendency in such directions is similarly and equally excluded, through the impossibility of explaining such cases by “community of descent.” (Mivart 1869, 45)

A gray whale with a mouth full of ~300 baleen plates: just one of the structural arrangements Mivart argued could not be explained by incremental natural selection

Mivart’s Dilemma is sometimes described as the idea that “organs of extreme perfection” cannot arise by the selection of minute variations. The term refers to highly complex organs requiring a large number of coordinated parts to function: think of the vertebrate eye, with its membranes, humors, musculature and neural apparatus. But if an organ can only function when many parts are jointly active, then it is difficult to see how selection could have formed the organ by the preservation of slight variants. The reason is that a happy variation— the formation of a proto-lens, say— would only confer an advantage on its possessor if many other features were also present— transparent membranes, photoreceptive cells, musculature to support the lens, etc. Yet when we are considering the initial formation of complex organs, we are considering a situation when these other features are not present. So this happy variation would in fact be useless, and could not be seized upon by selection.

This line of reasoning is cogent, and Darwin took it seriously. (Recall his concession that the incremental evolution of the vertebrate eye, “with all its inimitable contrivances… seems, I freely admit, absurd in the highest degree.”) Still, there is no reason to regard Mivart’s Dilemma as exclusively concerned with organs of extreme perfection. The inability of selection to account for the beginnings of highly complex organs is a special case of Mivart’s Dilemma— one that also involves the formidable problem of “coadaptation” (Ridley 1982). However, as Ridley says, coadaptation is just one dimension of a multifaceted debate regarding the efficacy of natural selection in evolution. And while it is true that Mivart discussed complex organs in the Genesis of Species (e.g., 50; 57–61), it is preferable to define his “dilemma” more generally, in holding with Mivart’s preferred formulation (Mivart 1869, 41; 1871, 251–252). An example will illustrate the distinction.

Among the strongest arguments in the Genesis of Species concerned the “wandering eye” of pleuronectiform flatfishes, a large order of ray-finned fishes that look like scaly pancakes (Mivart 1871, 41–43). Larval flatfishes are bilaterally symmetrical, and look to all the world like most other teleostean fishes. Yet during larval metamorphosis, a curious thing happens— one eye migrates to the opposite side of the fish’s head, finally settling next to the other eye. Soon afterwards the fish abandons perpendicular life forever, rotating 90° about its dorsal plane and wending its way on the seafloor with both eyes facing upwards. (Notice that while this example involves an organ of extreme perfection— the eye— it is not about how this organ originated: only how it shifted position. So, Mivart’s Dilemma is not the same as the problem of how organs of extreme perfection can arise.)

A pleuronectiform flatfish with two eyes on a single side of its head

In Genesis, Mivart puzzled over how this adaptation could have arisen by the accumulation of small variations, each conferring some incremental advantage on its possessor. He concluded that it could not: for what advantage accrues from an eye moving one millimeter upward, or even five? Of course, if the entire transit of the eye occurred in a single step, “then the perpetuation of such a transformation by the action of ‘Natural Selection’ is conceivable enough” (Mivart 1871, 42). But this is not Darwin’s method of transformation, and anyway, such a modification would leave the fish discombobulated without a range of other changes that fit it for life on the seafloor (the problem of coadaptation, which Mivart does not here mention). This led Mivart to conclude that the transformation could not be explained on Darwinian grounds.

It bears repeating that Mivart’s dilemma had to do with the competence of a cause (natural selection) to produce an effect (a particular morphological outcome or trajectory). This made the dilemma more than just an epistemological argument, as Mivart recognized. “It may be objected,” he writes, “that [the difficulties here mentioned] are difficulties of ignorance—that we cannot explain them because we do not know enough of the animals” (Mivart 1871, 59). But “[it] is not that we merely fail to see how Natural Selection acted, but [rather] that there is a positive incompatibility between the cause assigned and the results” (emphasis added). To surmount the problem of beginnings, something more than just natural selection was required. That was the nub of Mivart’s dilemma.

Synopsis

I have just distinguished three arguments that purported to show that natural selection is powerless to explain the origin of novel characters:

Nägeli’s Argument: Evolution involves the origin of new organs and structures, but natural selection can only preserve or destroy existing variation. So natural selection cannot be responsible for the origin of new organs and structures.

Jenkin’s Argument: Factors intrinsic to the organization of living things confine variation within certain limits (or “spheres of variation”). So natural selection cannot fashion new features (since this would involve breaching these spheres)— it can only improve what already exists.

Mivart’s Dilemma: Some evolutionary changes involve incipient stages that confer no advantage on their possessors. But the origin of features by natural selection requires that each stage in the process confer some advantage on their possessors. So selection cannot account for these changes, and therefore cannot explain the origin of (many) features that are useful in their developed states.

In addition, I discussed a fourth argument, which, although it has broad implications for evolutionary theory, functions as an auxiliary to Jenkin’s argument in discussions of evolutionary novelty:

Jenkin’s other argument (the swamping argument): Natural selection is unable to fashion new organs because (i) selection on the end of a range of continuous variation generates only quantitative change (subject to constraints imposed by intrinsic limits to variability; see “Jenkin’s Argument”) and (ii) “single variations” (unusual, discontinuous changes) will blend away due to interbreeding in populations of mostly unmodified individuals.

Finally, I observed that these four arguments, while logically distinct, were frequently presented together as a kind of self-reinforcing bundle. An example of this is provided by Theodor Eimer:

I must, in fact, reiterate again and again that natural selection can under no circumstance create anything new. It can only work with existing materials [Nägeli’s Argument], and it cannot even use that until it has attained a certain perfection, until it is already useful [Mivart’s Dilemma]. Selection can only remove what is downright injurious, and preserve what is useful. By always selecting the useful it will strengthen its development, but the facts prove that even this can take place only in a restricted measure [Jenkin’s Argument and/or Jenkin’s other argument]. Primarily, therefore, the importance of selection consists not in its being an active and principal agency in the transmutation of forms but in its being at most a simple collateral instrument in this process. (Eimer 1898, 21)

We will encounter Eimer again in Part 2 of this essay. There I will defend the claim I made above: that Mivart’s dilemma, in addition to being the most compelling of the arguments here reviewed, played the largest role in structuring attitudes towards Darwinism during the decades immediately following Darwin’s death.

A coda on the troubles and salvation of St. George Mivart

Mivart, photographed near the end of his life

Although Mivart was able scientist and critic, he was seemingly unable to get out of his own way. It is hard to know whether this owed to some flaw in his character (Darwin’s view), or whether he was genuinely unaware of his tendency to overstep. As evidence for the latter view, Mivart seems to have been taken aback by the reception of several offending statements, in particular, an 1874 slur of Charles Darwin’s second son, George. Had this been an isolated incident, it might have gone unpunished, and had Mivart shown the appropriate contrition, he might even have recovered his standing with members of Darwin’s inner circle. As it happened, the attack was just the latest in a string of missteps, the first of which was a belligerent review of The Descent of Man in the Quarterly. According to Mivart’s biographer:

The tone of the article is different from that of the Genesis. Where the latter, even at its most critical, was warm, friendly, and congenial, the former was bitter, overbearing, and condemnatory. While only tinges of the personal appear in the Genesis, the review is saturated with personal bias. This difference, both in tone and in argumentative approach, reflects Mivart’s decision to combat the false application of Darwinism to man with every weapon at his disposal. (Gruber 1960, 79)

After slandering George Darwin (again in the Quarterly), the fallout was quick and severe. Huxley cut off all communication with his former student after hauling him over the coals in a letter. Their association would not resume for a further ten years, and would never again transcend simple pleasantries. Others, like Joseph Hooker, never forgave him, as evidenced by his efforts to bar Mivart from the Athenaeum Club. In Adrian Desmond’s words:

The punishment would have been out of all proportion had the crime been solely scientific. But Mivart’s untimely and unexpected pledge of support of the despised Platonism stabbed at the very heart of the new movement; a fact made worse by his almost becoming one of Darwin’s inner circle. His precipitous desertion called for a show of strength, as much to warn the faithful as frighten the offender. Mivart thus found himself excommunicated by bell, book (The Origin) and candle, as he was later to be by the church himself (Desmond 1982, 141).

The flogging Mivart suffered at the hands of the Darwinians permanently damaged his scientific reputation. But evolution was never the centerpiece of his philosophy. That position was occupied by Catholicism, and as the years rolled on he began to have increasing problems with the church as well (Mivart 1887, 1892). “Catholics, to be logical, must say to any Roman congregation which should attempt to lay down the law about any branch of science: ‘You have blundered once, and we can never trust you again in any scientific matter,” Mivart fumed:

You may be right in your dicta, but also you may be wrong. The only authority in science is the authority of those who have studied the matter and are “men in the know.” As to all that comes within reach of inductive research, you must humbly accept the teachings of science, and nothing but science. And for this you should be grateful. (Mivart 1900a, 61–62)

It is befitting that a wrangler like Mivart should go out on his own terms. Following the Dreyfus affair, which roused him to righteous anger, he abandoned in turn the doctrine of infallibilism, the Catholic dogma of Hell, the Christian code of ethics, and finally, belief in the divinity of Christ (Mivart 1899, 1900b). Writing to a friend in 1900, he had this to say:

As to the character of Jesus Christ, I have during my long illness made as careful a study of it as I could, and I think the sentiment so many feel about it is due to traditional reverence and what they have been taught from infancy. What God incarnate did and said I used to reverence as divine and never criticized. But calm judgment of Jesus Christ as a mere man is a different matter. St. John’s account I put aside as ideal and fictitious. Of what we read in the Synoptics how much is true history? But if we accept most of it, it seems to me that certain parts are admirable, some teaching distinctly immoral, and other parts ignorant and foolish. Altogether had I lived then, I do not think he would have attracted me. (Mivart to Meynell, 1900, quoted in Gruber 1960, 212)

“Liberavi animam meam, I have freed my mind and my spirit.” In the ruins of his life’s work, amid the pale embers of a dying faith, Mivart had found some measure of salvation.

Four years after his burial in London, his remains were reinterred in a Catholic cemetery.

References

Bateson, W. 1894. Materials for the Study of Variation, Treated with Respect to Discontinuity in the Origin of Species. New York: Macmillan.

Bateson, W. 1909. Heredity and variation in modern light. In A.C. Seward (ed.), Darwin and Modern Science: Essays in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Birth of Charles Darwin and the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Publication of the Origin of Species, 85-101.

Beatty, J. 2016. The creativity of natural selection? Part I: Darwin, Darwinism, and the Mutationists. Journal of the History of Biology 49:659–684.

Bigoni, F. and Barsanti, G. 2011. Evolutionary trees and the rise of modern primatology: the forgotten contribution of St. George Mivart. The Journal of Anthropological Sciences 89:93–107.

Bowler, P. J. 1983. The Eclipse of Darwinism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bowler, P. J. 1996. Life’s Splendid Drama. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Carroll, S. B. 2006. The Making of the Fittest: DNA and the Ultimate Forensic Evidence for Evolution. New York: W. W. Norton and Co.

Conn, H. W. 1887. Evolution of To-day. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons The Knickerbocker Press.

Conn, H. W. 1900. The Method of Evolution. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons The Knickerbocker Press.

Cope, E. D. 1887. The Origin of the Fittest: Essays on Evolution. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

Desmond, A. 1982. Archetypes and Ancestors. London: Blond and Briggs.

Eimer, T. 1898. On Orthogenesis, and the Impotence of Natural Selection in Species Formation. Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Company.

Gould, S. J. 1991. Fleeming Jenkin revisited. In Bully for Brontosaurus. New York: W. W. Norton and Co.

Gould, S. J. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gruber, J.W. 1960. A Conscience in Conflict: The Life of St. George Jackson Mivart. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hoquet, T. 2024. Beyond blending inheritance and the Jenkin myth. Journal of the History of Biology 57:17–49.

Jenkin, F. 1867. ‘The Origin of Species’ [review]. The North British Review 92:277–318.

Kellogg, V. L. 1907. Darwinism To-day. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

Love, A. C. 2005. Explaining evolutionary innovation and novelty. PhD dissertation: University of Pittsburgh.

Lull, R.S. 1920. Organic Evolution. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Mivart, S. J. 1969. Difficulties on the theory of natural selection. The Month 11: 35–55, 134–153, 274–289.

Mivart, S. J. 1871. On the Genesis of Species. London: Macmillan & Co.

Mivart, S. J. 1899. The Dreyfus Affair and the Roman Catholic Church, letter to the Times (London), October 17, 1899.

Mivart, S. J. 1900a. The continuity of Catholicism. The Nineteenth Century 47: 51–72.

Mivart, S. J. 1900b. Roman congregations and modern thought. The North American Review 170: 562–574.

Morgan, T. H. 1903. Evolution and Adaptation. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Morgan, T. H. 1916. A Critique of the Theory of Evolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Morris, S. W. 1994. Fleeming Jenkin and “The Origin of Species”: a reassessment. The British Journal for the History of Science 27:313–343.

Nägeli, K. 1865. Enstehung und Befriff der Naturhistorischen. Munich: K. Bayr. Akademie.

Osborn, H. F. 1891. Are acquired characters inherited? The American Naturalist 25:191–216.

Rainger, R. 1991. An Agenda for Antiquity: Henry Fairfield Osborn and Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, 1890-1935. University of Alabama Press.

Ridley, M. 1982. Coadaptation and the inadequacy of natural selection. The British Journal for the History of Science 15:45–68.

Root, J. D. 1985. The Final Apostasy of St. George Jackson Mivart. The Catholic Historical Review 71:1–25

Vorzimmer, P. J. 1970. Charles Darwin: the years of controversy. New York: Temple University Press.