* This is the latest installment of “Problematica.” It is, in a way, a continuation of my three-part series on periodic diastrophism in American geology (Part 1– Part 2– Part 3). As I observed in that series, the theory of periodic diastrophism was widely credited in American geology during the first half of the twentieth century. This led me to wonder how it figured into debates over continental drift in the 1920s and ‘30s. The following is my attempt to grapple with that question. Problematica is written by Max Dresow…

Who today remembers Charles Schuchert? He was, for a time, a major figure in American geology, and did more than anyone else to launch paleogeography as a proper scientific enterprise. Each year the Paleontological Society gives the Schuchert Award to a promising young researcher. The list of past winners reads like a who’s-who of recent paleontological standouts. Schuchert’s biography is not without charm. He was one of the last people to rise in American science without even a high school diploma, and he weathered considerable hardship as a young man, including a fire that claimed the family business and indirectly, it seems, the life of his father. Charles responded by rebuilding the business before departing to work for the great despot of American geology, James Hall of Albany. (This was after a second fire claimed the Schuchert factory in 1884.) He achieved the very pinnacle of professional success when he secured a professorship at Yale and later became president of the Geological Society of America. Still, when he is remembered today it is almost always for one thing. This was his outspoken, and in hindsight unfortunate, opposition to the theory of continental drift.

Charles Schuchert, and a “Generalized map of America during Paleozoic time,” showing exposed land in white, geosynclinal basins in dark shading, and “the extensive neutral medial area” (shallow epicontinental seas) in light shading. From Schuchert (1918)

I wrote about Schuchert in a recent three-part essay on the influence of periodic diastrophism in geology. There I noted that he was, along with many of his most distinguished contemporaries, a disciple of Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin. I didn’t know much about Schuchert going in— actually, I knew him almost entirely as an opponent of drift, courtesy of Naomi Oreskes, Robert Newman, and others. Yet by the time I was finished I wanted to know more. So I picked my copy of The Rejection of Continental Drift to remind myself of what Oreskes had to say about him.

This essay was sparked by that reading, as well as my research for the diastrophism series. It advances one (not-so) big claim: namely, that Oreskes doesn’t get Schuchert quite right, and in a way that complicates her treatment of the rejection of drift. Or perhaps simplifies it? What I will argue is that we can strike one contributing factor from the list of factors Oreskes implicates in the American rejection of drift. This simplifies things. But it also raises questions about what was going on with Schuchert and other admirers of Chamberlin who aligned against the drift hypothesis. These questions are mostly beyond the scope of this essay. Still, I will be pleased if, in the spirit of Oreskes’s own work, I can add some touches of realism to the portrait of a man who is now usually remembered as a black hat of the drift debate.

In the next section I discuss the historiography of the drift debate, focusing on Oreskes’s account of the American rejection of drift. Then I turn to Schuchert, and offer my attempted refinement of Oreskes’s analysis of Schuchert’s “uniformitarianism.” Finally, I offer a few short remarks on the role of uniformitarianism in the great drift debates of the 1920s and ‘30s.

Bristling at the end of history, or why the Yanks whiffed on drift

Some historical events have such heft that, like a supermassive object, they warp the very space around them. After the fact we can’t quite see straight. We feel ourselves bent by the weight of it, and when we cast our eyes backward, the past presents itself in a new aspect: all just relation. The alleged “Darwinian revolution” had this effect. In addition to tilting the nineteenth century itself, it bent historical understandings of the period in ways that lasted for generations. Suddenly figures like Cuvier and Owen were, in the first place, opponents of evolutionary thinking. Even Plato emerged as a villain for ideas mooted in the fourth century BCE (Mayr 1982). This is historical gravity at work, pulling all narrative into its ambit and shaping our understanding of the past by selective emphasis and, in some cases, by active distortion.

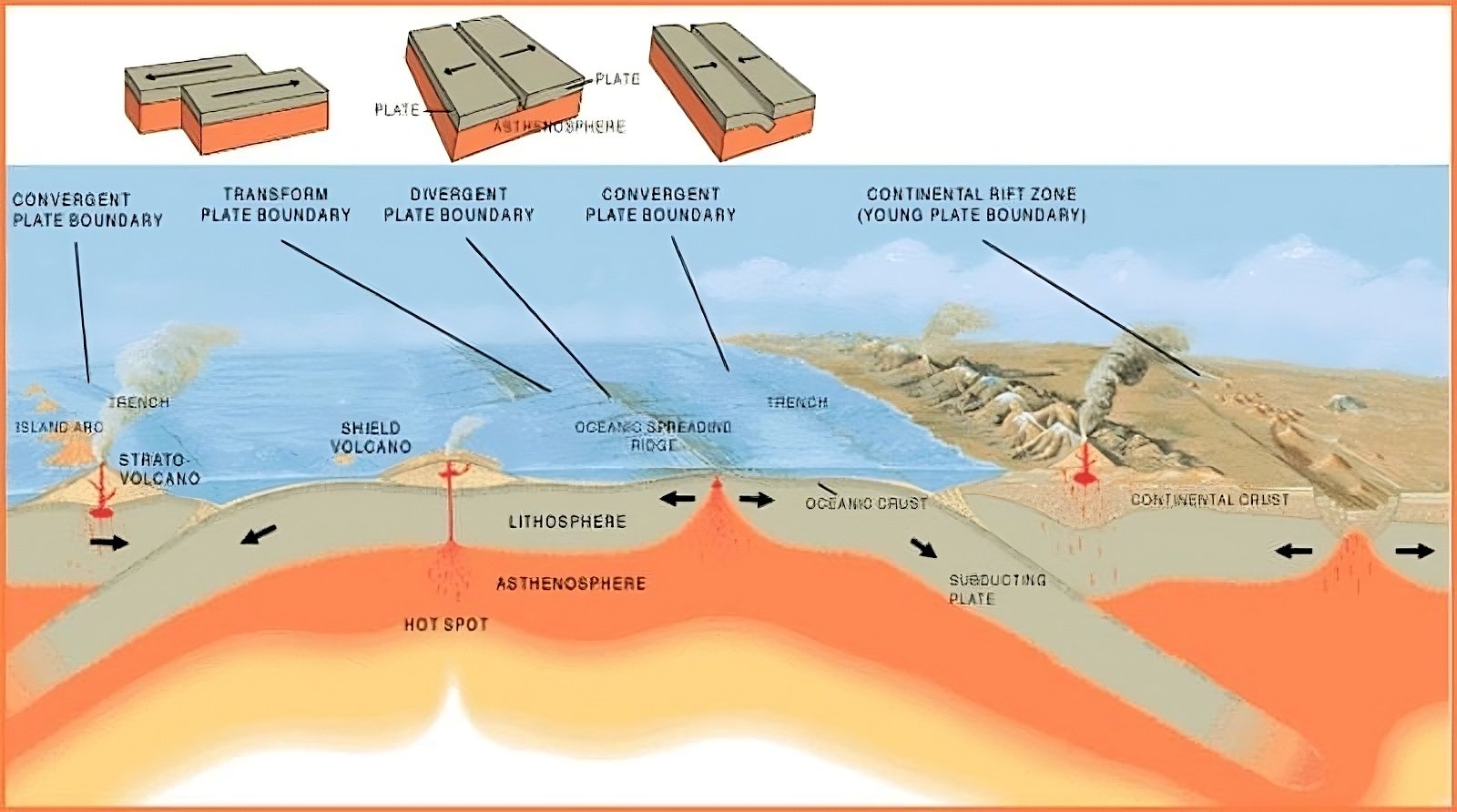

In the earth sciences in the twentieth century, the major gravitational event was the advent of plate tectonic theory.* It was, in a sense, the end of history. While much work was needed to flesh out mechanisms and attend to a million other details, the great truth of the solid earth had been revealed. It just explained so much. Just as Darwinian theory had explained everything from patterns of biogeography to the course of embryogenesis to the existence of vestigial organs, so plate tectonics explained everything from the distribution of major structural features to the clustering of volcanoes and earthquakes to patterns of biogeography (again!). A hundred geotheories had come and gone but this one was apparently here to stay. This was the sense in which the history of geology had, at last, come to an end.

[* I will follow convention here by treating “plate tectonics” as a theoretical framework that emerged in the 1960s and “continental drift” as a phenomenon that received its name during the second decade of the twentieth century.]

A now-standard textbook depiction of plate tectonic theory, highlighting types of plate boundaries

But the very rout that plate tectonics made of other geotheories raised a question. If plate tectonics was so obviously true— if it unified so vast an array of heterogeneous observations, and in a way that no other theory could even approximate— then why was “the drift hypothesis” so fervently resisted, especially in America? Many answers to this question have been given. It was rejected for want of a plausible mechanism. Because of American commitments to continental permanence. Because of anti-German sentiment. Because its champion, Alfred Wegener, wrote like an advocate. Because he had come to the idea through inspiration rather than perspiration. Because he mishandled some evidence. And anyway, was Wegner even a geologist? Basically, drift in America faced a whole raft of challenges, from pre-existing theoretical commitments to Great War-fueled xenophobia to misaligned methodological norms and standards of etiquette. None of these factors on its own provides a good explanation of Yankee intransigence. But put them all together and they acquire considerable explanatory force.

And yet the gravity of the plate tectonic revolution is such that it’s difficult to see the preceding period in natural light. Seen as it usually is, the period is one of heroes and villains, of those history would vindicate and those it would condemn. The temptation to moralize is apparently irresistible, and many have indulged it. Robert Muir-Wood, for example, has condemned the entire field of geology as retrogressive in contrast to geophysics, which incubated the revolution (Wood 1986). In Muir-Wood’s hands, geologists appear as hapless fuddy-duddies, in contrast to the “whole earth” geophysicists. His writing sparkles but his history sucks. There just isn’t a straightforward heroes and villains story here; the “heroes” are too flawed and the “villains” too endearingly human. Anyway, we should not let the gravity of plate tectonics so warp our perspective that we see everything in relation to it— even the basic standing of things like geology and field evidence. Moralizing about the past can be fun, but it gets in the way of understanding.

A plate from Wegener’s The Origin of Continents and Ocean (1924 edition), showing the location of the continents in the Upper Carboniferous, Eocene, and “older Quaternary,” respectively

The best treatment of the drift debate is, of course, Oreskes’s The Rejection of Continental Drift. It’s an impressive work, which, despite some missteps that apparently triggered her more sexist reviewers, presents a wealth of information and careful argumentation. Its most striking claim is that drift was not rejection for want of a mechanism: by 1929, Oreskes writes, “three powerful theories— Davy’s gravitational sliding, Joly’s periodic fusion, and Holmes’s subcrustal convection currents— had been developed to explain the kinematics of drift” (Oreskes 1999, 119). None of these required the continents to plow through an unmoving ocean floor; all were based on physical ideas that enjoyed some currency at the time.* So, whatever caused American geologists to align against drift, it was not that no one had described a mechanism capable of saying how continents had moved laterally over thousands of miles.

[* Oreskes does not suggest that any of these mechanisms was a vera causa (or demonstrably efficacious cause), and this means that it was open to geologists to reject drift because it was not associated with a vera causa of continental movement. But then, geologists had been reasoning about tectonic processes in the absence of verae causae for a long time. (Or had they? This is a difficult subject, since doubtless some geologists regarded the cooling and contraction of the earth, e.g., as a vera causa in virtue of its relationship to well-established empirical principles.)]

Naomi Oreskes these days

But what did cause Americans to align against drift? Oreskes’s preferred account has several components. One part was simple parochialism. American geologists as a group were proudly nationalistic, and believed that American research had provided the elements of a comprehensive geotheory. These elements were, in Mott Greene’s useful summary,

permanent oceans; geosynclinal basins growing on cratonal margins; compressional orogenesis of filled geosynclinal basins [that is, subsiding oceans crumpling the margins of stable continents], with earthquake-driven block-faulting creating the rest of the mountains; [and] isostasy permitting the up and down movements of continents… To explain faunal similarities across oceans they liked isthmian links (land bridges) because they had two of their own— the Bering Land Bridge and the isthmus of Panama. They even had their own cosmology—the Chamberlin-Moulton planetesimal accretion theory… All of this was underway by 1900 and steadily elaborated until the 1960s (Greene 1999, 341)

It’s worth emphasizing that these ideas, in addition to being American, were powerful and mutually-reinforcing— it’s not as if American geologists were theoretically adrift in those decades when the drift debate burned the brightest. As Rollin Chamberlin put the matter in 1928, quoting an unnamed colleague, “If we are to believe Wegener’s hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the last 70 years and start all over again.” This was an expression of confidence. Something of value had in fact been learned, and we should be loath to give it up.

A map of the geosynclines of North America in the Ordovician Period, from Marshall Kay’s 1951 monograph, North American Geosynclines. (Compare to Schucert’s “Generalized map of America in Paleozoic time,” above)

Then there was the work of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, which, for a variety of pragmatic reasons, came to interpret gravimetric data in line with a particular model of the earth’s crust. William Bowie, for example, interpreted these data as evidence that the crust was in a state of nearly complete isostatic equilibrium. This meant, for him, that the earth’s surface features “must have reached their present configuration early in earth history, so that there had been adequate time for equilibration” (Oreskes 1999, 169). Crust and mantle were nicely balanced, and the topographic relief achieved by crustal blocks varied inversely with their density— that was the model. From which followed a whole train of implications. Lateral movements of the crust were fairly small, and occurred in response to the erosion of mountain chains and the deposition of sediments in basins. Subcrustal flow took place from regions of sedimentation to areas of mountain building, where the application of compressive force caused uplift and maintained isostatic balance. It was, Oreskes argues, a remarkable development: a model “initially accepted for pragmatic reasons became a form of scientific practice” (177). Anyway, the upshot was that, for Bowie and his followers, continental drift became basically unthinkable.

But it wasn’t just in the domain of theory that American skin was in the game. In addition, American geologists had articulated their own standards of proper methodological conduct, which resonated with the pluralistic and democratic spirit of the nation. Here, Thomas Chamberlin’s “method of multiple working hypotheses” was especially influential (Chamberlin 1890). In one of the book’s strongest arguments, Oreskes presents the case that American geologists took these methodological injunctions very seriously, in part because they fit with larger cultural assumptions about the moral value of hard work. This drew the contrast with European geology, with its high authorities— the equivalent of a hereditary ruling class— given to dogmatic pronouncements:

If European science was autocratic and dogmatic, American science would be pluralistic and receptive. If Americans achieved commercial success through hard work, they would achieve scientific success the same way. And if Europeans achieved scientific rank through privilege or personal fortune, Americans would achieve it through diligence and commitment. (Oreskes 1999, 151)

The upshot for drift was that it was suspect because of how the theory was presented: not as one of several competing hypotheses, but as a new “ruling theory” proclaimed by an admitted advocate. Moreover, it was a theory arrived at by inspired guesswork and supported by a selective marshaling of relevant evidence— all sins in the eyes of American readers.

Alfred Wegener, the chief advocate of the drift hypothesis in the early going, in Greenland

Theoretical ideas, national pride, methodological pluralism— these are the not-entirely-separable components of Oreskes’s account. But then she adds one more thing: uniformitarianism. Here Schuchert takes center stage. According to Oreskes, Schuchert was amenable to the idea of drifting continents up to a point. But only to a point. While he was willing to grant lateral movements of “a few hundred miles,” to further admit that “North and South America have drifted to the west up to 5000 miles can only be acceptable to forgetful or deranged minds” (Schuchert to Molengraaf, 1923; quoted in Oreskes 1999, 202). The distinction seems arbitrary.* But it makes sense, Oreskes thinks, in light of Schuchert’s commitment to (substantive) uniformitarianism. This is “the belief, expounded most famously by Charles Lyell, that the earth today is more or less as it has always been” (Oreskes 1999, 200).

[* In fact, I suspect it is less arbitrary than it seems, since what Schuchert is most likely blessing is the idea that parts of continents move laterally in orogenic events and along certain faults— something most ‘fixists’ were willing to grant (see Oreskes 1999, 202).]

It’s a clever argument, and Oreskes presents it with great clarity and force. But I think it misrepresents Schuchert’s position in a subtle yet important way.

Charles Schuchert between uniformitarianism and diastrophism

To state the obvious, Charles Schuchert was not reliable when it came to drift. He didn’t like the idea; probably it compelled too large a revision in his belief system to ever pass muster. His career had been built upon the “new geology” of Thomas Chamberlin, which was incredibly popular at Yale at the time, including among his paleontological colleagues. Joseph Barrell, who Schuchert greatly admired, went to his grave a disciple of Chamberlin— reformed but not outside the circle. Apart from this, Schuchert was a proud American nationalist. It was all too much, and too late in life. So he resisted drift with all the powers at his disposal.

Schuchert is thus a plausible villain, and in many tellings of the trials of drift, he is cast in just this role. Certainly he exhibited behavior that did not recommend him to posterity as a model of scientific decorum. He was not above skullduggery when it came to refuting drift in print (see especially Krill 2011). And he was hardly consistent in avoiding the epistemic sins he charged others with (e.g., Schuchert 1928, 1932).

But this kind of behavior is hardly rare in the history of science. Lord knows there are plenty of examples in the history of geology of just this sort of thing (Rudwick 1985; Secord 1990). No, what makes Schuchert such a compelling villain is that he was wrong— loudly, brashly, self-righteously wrong, and about the most important thing ever. But, like, so what? It’s bad enough to be wrong. Does Schuchert also need to get dunked on for the rest of time? This much I know: dunking on him won't help us understand him. It’s because Oreskes knows this too that her discussion of Schuchert is uniquely stimulating. (Much more stimulating than Robert Newman’s contemporaneous account, which drips with righteous indignation.)

A map of the paleocontinents of the upper Carboniferous including a very broad Gondwanaland, based loosely on Suess’s reconstructions. From Wilhelm Bolsche’s Das Leben der Urwelt (1932)

Oreskes’s discussion of Schuchert’s uniformitarianism follows a fascinating account of his campaign to “get rid of Gondwana” (as he put it). Gondwana was the paleocontinent first posited by Eduard Suess to explain patterns of floral and faunal distribution in the southern hemisphere. Schuchert needed it to account for otherwise puzzling paleogeographic data. (Puzzling, that is, if continents don’t scoot about laterally.) But since Gondwana is no longer a continent, he also needed to get rid of it— and that was a problem, since on the theory of isostasy, light blocks of continental crust can’t just founder, as Suess had imagined. To get out of the pickle, Schuchert turned to Barrell, a brilliant geologist and geophysicist, to provide a mechanism for sinking a block of crust. And indeed Barrell obliged, reasoning that if light crust were “loaded” with basalt (by massive intrusions from the high-density substratum), then the crustal block would break up and sink under its own weight (e.g., Barrell 1918). This, he thought, could drown a land bridge connecting Africa to South America, or India— just the sort of thing Schuchert needed to sooth his troubled soul.

I won’t burden you with the rest of the story. Interested readers should consult Oreskes, who explains the whole episode in great detail and with many quotations from Schuchert’s correspondence. Suffice it to say that Barrell’s account didn’t hold up, and then Barrell himself succumbed to bacterial infection. This left Schuchert in need of a new tectonician, which he found in Bailey Willis. But before Schuchert and Willis co-published, Schuchert tried courting the prominent “drifter” Arthur Holmes; and this is where, in Oreskes’s view, Schuchert laid his uniformitarian cards on the table.

Schuchertʼs “Synthetic paleogeographic map of all Permian time,” picturing land bridges (in yellow) connecting South American and west Africa, South America and Antarctica, Madagascar and India, and parts of southeast Asia. Shallow seas are colored green. As Alan Krill (2011) notes, there was some chicanery involved in the production of this map, since the base projection Schuchert chose— the Goode homolosine projection— was the one that minimized the apparent distance between South American and West Africa. From Schuchert (1932).

The key piece of evidence comes from a letter Schuchert sent to Holmes in 1931. Schuchert had just read Holmes’s article, “Radioactivity and earth movements,” which summarized the Englishman’s ideas about convection currents and drift. The American was pleased that, as he saw it, Holmes had given him a mechanism for sinking parts of continents. (This, alas, was based on a misunderstanding.) But then Schuchert went on to explain why he preferred sunken continents to sliding ones:

Excuse me if I say so, as a marine faunal paleontologist and stratigrapher, that the weakest link in your convection hypothesis is that of continental drift. To move the British Isles in late Paleozoic time from the tropics to their present provision is to fly in the face of all the marine faunas. These biota are not tropical, while those of the Permian of northern Europe remind one far more of cooler waters than warm ones. Where in these lands are the coral faunas and reef limestones, the bryozoans reefs and the great thicknesses of limestones such as we look for in tropical regions? There are such now in the Mediterranean countries, and according to your hypothesis they must have originally been formed in the southern temperate regions. And yet, in the temperate regions the water would have been too cool to have permitted the making of great limestones and bryozoan reefs, and for the existence of an abundance of ammonites. (Schuchert to Holmes, 1931, quoted in Oreskes 1999, 199)

Here, Oreskes says, is “a uniformitarian demand,” but “it is uniformitarianism of a particular— even idiosyncratic— kind.” What Schuchert was demanding was “that ancient faunas and their associated climatic zones should show the same relation to latitude as do modern ones.” Otherwise, Schuchert would have no basis for saying that the absence of coral faunas and reef limestones militates against an equatorial location for Britain in the Paleozoic. She continues: “Despite all the evidence of climatic change in geological history, Schuchert’s view of climatic zones was essentially static. Waters in low latitudes were always warm, in high latitudes were always cool.” Schuchert, again:

As a paleontologist, I have no objection to your moving the continents about a few to several hundred miles, but when you demand thousands of miles, you drifters say to us workers on marine faunas that all that is known about faunal distribution is worthless. This means that the present distribution of marine faunas cannot be trusted, and cannot be applied to past life. (Schuchert to Holmes, 1931, quoted in Oreskes 1999, 199)

This is a remarkable passage. It’s obvious why Oreskes makes such a big deal out of it— in her words, the objection “makes no sense by contemporary lights.” Today we know that the equator has not always been hot, nor the poles swaddled with ice. “Yet this is what Schuchert believed. He subscribed to substantive uniformitarianism: the belief… that the earth today is more or less as it always has been” (200). Elsewhere Oreskes states that Schuchert’s belief in uniformitarianism “shaded into a belief in [absolute] uniformity” (201). “Uniformitarianism has meant many things to many people; [but] to Charles Schuchert in the late 1920s it meant… an essentially steady-state earth whose details were forever changing but whose large-scale patterns and relationships remained the same.”

One of Schuchert’s celebrated paleogeographic maps, this one of the early Cretaceous. This particular map is a kind of “living” draft, to which Schuchert made refinements over the course of many years. It was eventually published in the second edition of his Outlines of Geology (plate 28, map 1)

But Schuchert was not a substantive uniformitarian, at least in the sense indicated by Oreskes. Schuchert did not believe “that the equator has [always] been stiflingly hot [and] the poles… under glacial ice” (Oreskes 1999, 200). In fact, he believed with many of his contemporaries that the present world is climatically unusual. As he wrote in 1918:

We are living in a time when the earth has marked climatic differences, varying between icy polar climates and hot moist or dry tropical conditions. This, however, has not always been the case. (Schuchert 1918, 55)

Not long ago, “the temperature of the entire earth was even colder than it is now.” This, of course, referred to the Pleistocene glacial period. But that too was an unusual time, since “most of the climates of the past have been warm and fairly equable,” with basically constant conditions across the surface of the planet. The word “fairly” is doing some work here; Schuchert believed that “there were at all times zonal belts and fluctuating conditions,” the former caused by differences in the supply of incoming solar radiation. Yet he went on to claim that the polar areas were usually inhabited… by plants and animals that were adjusted to winterless environments.” So, while zonation has been a more-or-less constant feature of earth’s history, most geological periods have not closely resembled the present one.

A diagram from Richard Swann Lull’s “The pulse of life” (1918), whivch he prepared in consultation with his Yale colleagues Schuchert and Barrell. Most likely Schuchert contributed the curve of “climatic fluctuations,” and Barrell (along with possibly Schuchert) the “elevation” data. The thing to notice here is that the climate curve bifurcates at three points: once in the Permian (actually, the latest Pennsylvanian), once (briefly) at the Triassic-Jurassic transition, and once in the Miocene. These are the only intervals of time (according to the diagram) that aridity and cold were sharply differentiated, enabling ice to accumulate in polar latitudes

Oreskes’s analysis is by no means completely off-base. To postulate constant latitudinal zonation is not to postulate an absolute uniformity of conditions. Nor is it to take the present as the standard for all past times. But it is to posit, “that ancient faunas and their associated climatic zones should show the same relation to latitude as do modern ones.” With some exceptions. Apparently, polar latitudes cannot be counted on to host sea ice; more often than not they will be “winterless.” But they can be expected to be cool, even in times of equably warm conditions. Is this a coherent thought? Maybe not, and maybe this means that Schuchert was more of a uniformitarian than he realized. Still, it is not correct to say that he believed in a completely steady-state earth, or that he tended to downplay or ignore evidence of past climatic change.

Quite the opposite in fact. Schuchert took past climatic change very seriously. All geologists influenced by the theory of periodic diastrophism did. In this system, which bound together orogeny, climate, and evolution, climatic change was a function of the same processes that created topographic relief and carved geological time into natural units. Schuchert explained how it all hung together:

The very long warm times [characteristic of most geologic periods] were separated by short periods of cool to cold climates. Geologists now know of seven periods of decided temperature changes (earliest and latest Proterozoic, Silurian, Permian, Traissic-Lias, Cretaceous-Eocene, and Pleistocene), and of these the last four (those in italics) were glacial climates). Cooled climates occur when the lands are largest and most emergent, during the closing stages of periods and eras, and cold climates nearly always exist during or immediately following the times when the earth is undergoing most marked mountain making. (Schuchert 1918, 55)

Now, there’s a sense in which one can talk about this picture as a steady-state one. That is, the climatic history of the earth is here pictured as relatively stable despite regular perturbations. Over large stretches of time, the planet tends to behave as if a thermostat had been set to “warm and equable.” It’s not a very Lyellian picture, but it is, I suppose, “uniformitarian.” The earth is a system that regularly perturbs itself by rhythmic pulses of mountain-building. These pulses cause the onset of “cool to cold climates.” But conditions (usually) return to normal pretty quickly. Again, this isn’t Lyellian, but I don’t object to calling it “uniformitarian” in some sense.

Schuchert’s diagram of the history of climatic fluctuations, on the one hand, and diastrophic pulses (“disturbances” and “revolutions”), on the other. Notice how relatively anomalous the present period of time is. From Schuchert (1918)

Still, two things about Schuchert made him less than the stability-monger of Oreskes’s portrait. First, he was not concerned to de-emphasize the importance of climatic perturbations, notwithstanding their relative infrequency. To the contrary, he regarded these pulses of refrigeration as no less important than the much longer periods of warmth and repose that separated them. This is because they were responsible for delimiting major intervals of geological time and for filling and draining epicontinental seas— two things that mattered to him as a stratigraphic and paleogeographer. Second, Schuchert regarded the present world, with its towering mountains, as an extremely perturbed world— indeed, as highly anomalous. This, admittedly, did not extend to all its features. The association of faunas with climatic zones could apparently be projected backwards to understand much flatter and hotter worlds; hence the exchange with Holmes. Still, if a (substantive) uniformitarian is someone who regards the present world as a good model for all past times, Schuchert does not fit the bill. He was something else— a “diastrophic uniformitarian,” if you like, although this should not be taken to imply that he thought mountain-building (e.g.) was happening all the time. The last was Lyell’s view. Schuchert thought differently.

* * *

Some of you will probably think I’m splitting hairs, and I suppose I am. But this is why I’m doing it. Oreskes claims— or at least she has been taken to claim— that an American commitment to uniformitarianism was one of the things that caused them to whiff on drift. Here is Mott Greene, again:

In Oreskes account, it was not just that [American geologists] were wedded to a ‘made in America’ theory, but that they were even more fatally bonded to two principles of method: ‘multiple working hypotheses’ and ‘uniformitarianism,’ which were interpreted by defenders of the American theory in a way that ruled out European hypotheses generally, and mobilist hypotheses in particular (Greene 1999, 341)

Now, in the case of multiple working hypotheses, Oreskes has lots of evidence that this was a contributing factor in the rejection of drift. But what is the evidence that uniformitarianism shoulders some responsibility? Just that it was allegedly a major factor in Schuchert’s unwillingness to entertain drift as a live option. And I’m not sure that it was. Schuchert did believe that latitudinal zonation was a constant feature of the earth’s climate, even during the equably warm phases that have dominated geohistory. And this implied that certain of Wegener’s reconstructions couldn’t possibly be correct. But to say that all this was down to Schuchert’s “uniformitarianism” is at best an idealization. At worst it is a distortion of what Schuchert really believed.

Here’s what I mean. In her discussion, Oreskes states that “Many geologists— of whom Schuchert was one— came to feel as if good science required one to aim in the direction of Lyellian explication as far as possible” (Oreskes 1999, 201) This makes it seem as if Schuchert was a disciple of Lyell, and in particular, that he resisted “those who argued for… large-scale or sudden change,” in contrast to the slow and steady drumbeat of gradual change. Yet Schuchert’s major influence in the domain of geotheory was not Lyell but Thomas Chamberlin— a rather un-Lyellian figure who supported large-scale and (relatively) sudden change! Try to imagine Lyell writing this (in fact, it is Schuchert describing some ideas he inherited from Chamberlin):

Finally, there comes a time of major shrinking [of the earth] that adjusts all of the strains and stresses set up in the earth’s mass by the minor, incompletely adjusted shrinkages. The earth has just passed through one of these major readjustments, and accordingly we see all of the continents standing far higher above sea-level than has been the rule throughout geologic time, and in many of them rise majestic ranges of mountains. A grander, more diversified, and more beautiful geography than the present one the earth has never had; this statement is made advisedly and with the knowledge that our planet has undergone at least six of these major readjustments of its mass. These greater movements are the “revolutions” that close the eras. (Schuchert 1918, 71)

Of course, we can question how much of this picture Schuchert retained into the 1930s, but I would bet that he retained a good part of it. (As I argued in an earlier post, periodic diastrophism remained a leading idea in American geology into the 1940s.) At any rate, the fact that he ever held these views discredits the idea that his paleogeographic practice was built on “substantive uniformitarianism.” It was built instead on periodic diastrophism and the associated doctrine of continental permanence: two ideas that were linked in the writings of Thomas Chamberlin.

All of which leads me to doubt that “uniformitarianism” had any distinctive role to play in the American rejection of drift.

Last thoughts

Having said this, let me close the essay by immediately qualifying it in two ways. First, it is demonstrably the case that uniformitarian strictures played a rhetorical role in the drift debates of the 1920s. The role was a small one, but it was real enough. Edward Berry, for example, tried to score points in a hysterical campaign against drift by painting the hypothesis as “cataclysmic.” In his contribution to the famous 1928 AAPG symposium, titled “Shall we return to cataclysmic geology?,” Berry wrote the following:

I had innocently supposed that the Revolutions of the Globe, so much a part of early geological thought… had been decently dead and buried these many years, through the labors of Lyell and others, but they continue to stalk up and down in disembodied form like the ghost of Hamlet’s father. And the ghost’s repeated injunctions to swear is amply warranted when we view the Wegener hypothesis, ‘our mobile earth’ and the disturbances and revolutions punctuating geological time table as it is taught in the majority of colleges and universities. (Berry 1929, 3–4)*

And here is Arthur Keith, a future president of the Geological Society of America, speaking in a GSA symposium in 1922: “[Wegener’s] hypothesis apparently must, therefore fall back on a cause which is of the order of the special convulsion of nature appealed to in the early stages of geologic work. Such a convulsion of nature, which affected a whole hemisphere, could have no probable cause except one of an astronomical nature” (Keith 1923, 361). Wegener had made no claims of astronomically-driven convulsions; the closest he came was to appeal to axial precession as a possible cause of drift. But insofar as Keith could imagine none but a convulsive cause, Wegener’s proposal could be slandered as a revival of old school catastrophism.

[* Berry— who was a true Lyellian— did not just go after Wegener and Reginald Daly (the author of Our Mobile Earth). He also went after the diastrophists. The language of “disturbances and revolutions” was theirs; in fact, Barrell (1917) said it came from Schuchert.]

Arthur Holmes’s proposed mechanism for continental movement (and rifting). From Holmes (1931)

The second sense in which uniformitarianism factored in the drift debates has already been mentioned. For some geoscientists, the decisive objection against drift was the lack of a demonstrably efficacious cause of lateral continental movement. Of course, several candidate causes were on offer, and as Oreskes says, these were consistent with the best contemporary thinking in geophysics— they were live options. But they were all more or less speculative, and this meant that epistemically cautious geologists had reason to mistrust them. There is a question about how consistent this was. After all, these scientists likely put their trust in causes that were, in the last analysis, no less speculative. But whatever. The point is just that some scientists rejected drift for want of a vera causa, while also believing themselves to be in possession of a vera causa of mountain-building, climatic change, and so forth.

This essay has been a plea to treat the traditional villains of the drift debate with a measure of sympathy. I admit this is not always easy. Berry’s rhetorical flourishes are, frankly, super annoying. And Schuchert often comported himself with the haughtiness of a true patrician. At this point historical gravity takes over. These men become villains because they took the wrong side in the only debate they participated in that really mattered. Understanding recedes in the face of moral condemnation. But we should not fall into the trap of thinking that continental drift was so obviously true that only stupidity or vice could explain strong resistance. Schuchert clearly did not like the drift hypothesis, and fought wildly against it. But he fought because, for him, the stakes were high. Our job is to understand these stakes in all their complexity and, perhaps, incongruousness.

References

Barrell, J. 1917. Rhythms and the measurements of geologic time. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 28:794–904.

Barrell, J. 1918. The origin of the earth. In R. S. Lull (ed.) The Evolution of the Earth and its Inhabitants: A Series of Lecture Delivered before the Yale Chapter of the Sigma Xi during the Academic Year 1916–1917, 1–44. New Have: Yale University Press.

Berry, E. W. 1929. Shall we return to cataclysmal geology? American Journal of Science 77:1–12.

Chamberlin, R. T. 1928. Some of the objections to Wegener’s theory. In Theory of Continental Drift. Tulsa: American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

Chamberlin, T. C. 1890. The method of multiple working hypotheses. Science 15:92–96.

Greene, M. 1999. Reviewed Work(s): The Rejection of Continental Drift: Theory and Method in American Earth Science by Naomi Oreskes. Earth Sciences History 18:336–343.

Holmes, A. 1931. Radioactivity and earth movements. Transactions of the Geological Society of Glasgow 27:567–606.

Kay, M. 1951. North American Geosynclines. Baltimore: Waverly Press, Inc.

Keith, A. 1923. Outline of Appalachian Structure. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 34:309–380.

Krill, A. 2011. The chicanery of the isthmian links model. Earth Sciences History 30:200–215.

Lull, R. S. 1918. The pulse of life. In R. S. Lull (ed.) The Evolution of the Earth and its Inhabitants: A Series of Lecture Delivered before the Yale Chapter of the Sigma Xi during the Academic Year 1916–1917, 109–146. New Have: Yale University Press.

Mayr, E. 1982. The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution and Inheritance. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press.

Muir-Wood, R. 1986. The Dark Side of the Earth. New York: Allen & Unwin.

Newman, R. P. 1995. American intransigence: the rejection of continental drift in the great debates of the 1920s. Earth Sciences History 14:62–83.

Oreskes, N, 1999. The Rejection of Continental Drift: Theory and Method in American Earth Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schuchert, C. 1918. The earth’s changing surface and climate during geologic time. In R. S. Lull (ed.) The Evolution of the Earth and its Inhabitants: A Series of Lecture Delivered before the Yale Chapter of the Sigma Xi during the Academic Year 1916–1917, 45–81. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schuchert, C. 1928. The hypothesis of continental displacement. In Theory of Continental Drift. Tulsa: American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

Schuchert, C. 1932. Gondwana land bridges. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 43:876–915.

Secord, J. A. 1990. Controversy in Victorian Geology: The Cambrian-Silurian Dispute. Princeton: Princeton University Press.