In which Max complains about how prevalent the language of political domination is in popular writing about dinosaurs

Read MoreRemeasuring Pisanosaurus

The most important dinosaur no one has ever heard of might not really be a dinosaur

Read MoreFrom the War of Nature

Derek Turner writes . . .

What if our representations of dinosaurs sometimes say more about us than about the animals themselves?

Why, for example, do we so frequently represent dinosaurs as fighting? One classic example of this is Charles Knight’s famous painting of the gladiatorial face-off between Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex.

T. rex couldn’t really box, but look at how the animals are squaring off like prizefighters on opposite sides of the ring. Or like cowboys facing off at high noon. We’re looking at dinosaurs, but the ritual being enacted here is familiar. And human. I observed many fights when I was in junior high school, and every single one of them started with a ritualized face-off, just like this. Or like this:

The trouble (as Brian Switek explains here), is that there is not a shred of evidence that such duels ever actually happened. That bears repeating: THERE IS NO EVIDENCE THAT TRICERATOPS EVER ENGAGED IN COMBAT WITH T. REX. There are a few suggestive tooth marks in Ceratopsian frills, but toothmarks do not necessarily imply combat, since they could easily have been made post-mortem.

None of this is to say that representations of T. rex fighting Triceratops are inaccurate. The point is that such representations are only loosely constrained by the empirical evidence. Even as our understanding of dinosaurs has changed a great deal, certain ways of representing them have remained deeply entrenched. For example, this was the cover of a book that was one of my own favorites, when I was a kid:

But even as scientists like Robert Bakker led the dinosaur renaissance in the 1980s, the dueling dinosaur motif persisted.

Seen in historical context, there is nothing terribly heretical about the depiction of dinosaurs fighting.

Prehistory as a Mirror for Humanity

The evidential slack means that that there is room for us to read our own human foibles and predilections back into nature. We reconstruct prehistoric life—and dinosaurs in particular—in our own violent image.

In an earlier post, I suggested that part of what draws us back to the Mesozoic is nostalgia for a wilder world where humans have no place. But we also populate that wilder world with animals that can seem a lot like us, animals that wasted their time on Earth in perpetual conflict and combat. My claim is that representations of prehistoric life can function as a mirror that shows us something about ourselves, if obscurely.

Recently on a visit to Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, I saw a (quite famous) dinosaur skeleton that, amazingly, drove both of these points home at the same time. It was Deinonychus—a specimen that, interpreted by John Ostrom, helped to launch the dinosaur renaissance. But there's poetry in the decisions about how to mount the skeleton:

The animal is pouncing, in the middle of an attack. The dynamic pose contrasts with earlier representations of dinosaurs as sluggish, such as Knight’s painting. But combat is the common thread. Why not portray Deinonychus as sitting, or napping? Many predators spend most of their time lazing around. One part of the answer is that we like to watch violence. Another part of the answer is that we like being told that our own violent tendencies are natural.

What is Deinonychus pouncing on? You! The museumgoer. Even though it’s just a skeleton suspended from the ceiling, the museum exhibit places you, the visitor, in the wilderness before time, where animals like Deinonychus might leap at you and eat you. The exhibit places you in a fight with a dinosaur, and one that you are guaranteed to lose. There is a fascinating double movement here: the exhibit cuts humanity down to size, but the animal doing the slashing is strangely humanized. It is using its weapons to attack you in the way another person might do.

Dinosaur Weaponology

This obsession with dinosaur fighting also, I suggest, has some impact on paleontological research. A lot of work goes into the functional morphology of dinosaur weapons. Consider the thick cranial domes of some pachycephalosaurs. In the dinosaur books I loved as a kid, the animals were often portrayed like this:

These, presumably, are males, ramming each other into submission to see who gets the territory, or the females. The thick skulls evolved by sexual selection. Or so the story goes.

Along the way, however, some scientists have expressed skepticism about this picture. For example, Kenneth Carpenter argued (here) that the tops of pachycephalosaur skulls have too little contact area for the head butting to work. Instead, he hypothesized that the animals must have engaged in "flank butting." Others have wondered about the morphology of pachycephalosaur necks. Was the curvature of the neck vertebrae well designed for withstanding impacts? Perhaps the skulls were instead used for display or recognition. Meanwhile, other researchers have looked at pathologies--at the frequency of bone lesions in pachycephalosaur skulls--and argued that those are suggestive of injuries due to head-butting. Debates about the head-butting hypothesis have also gotten plenty of public attention.

My worry about all this is not that the head-butting hypothesis is wrong. My worry is just that there is so much attention lavished on research on dinosaur weapons--and on what are thought to have been male weapons, at that. There are lots of interesting questions that could be asked about pachycephalosaurs--about their ecology, about other aspects of their behavior--and yet it almost seems like the only thing we see when we look at the animals are their weapons. When dinosaur weaponology research gets disproportionate public attention, that creates the impression that the weapons were their most important features. Indeed, we often treat dinosaurs' weapons and armor as their defining features. But there's no deep reason why we have to do that.

Stereotypes about Dinosaurs?

We also represent dinosaurs in a way that showcases their weapons. If you take time to observe carnivores—your pet dog counts, as do the backyard coyotes—you might notice that they do not spend much time with their mouths hanging open. If we wanted to, we could adopt a practice of always portraying dogs like this:

But this would be a kind of reputational injustice to dogs. The representation isn’t exactly wrong—dogs do sometimes act like this—but it’s biased. Just try, however, to find a museum exhibit in which a carnivorous dinosaur is reconstructed with its mouth closed.

There are interesting cases where people have messed up stereotypes about other animals. (Actually, these can interact in complex ways with stereotypes about people. These are complicated issues, but this book by Vicki Hearne might be one place to start exploring them.) For example, many people think of pit bulls as especially ferocious and aggressive dogs. But people who’ve hung out with snuggly, well cared for pit bulls know otherwise. It's not even entirely clear what breed, if any, the term "pit bull" is supposed to pick out. They are just dogs. Perhaps we are guilty of stereotyping dinosaurs in somewhat the same way.

From the War of Nature

This tendency to read of our own interests and predilections back into nature is nothing new. Darwin did the same thing. Many people have cited the famous closing sentence of the Origin of Species, the one that opens with, “There is a grandeur in this view of life . . .” For many years, Stephen Jay Gould wrote essays for Natural History magazine under the heading, “This View of Life.” However, the sentence that precedes the famous closing line is just as revealing--and, I would argue, kind of problematic. Here it is:

“Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows”

(p. 425. All page numbers are from this version of the Origin, which is available online.)

Nor is this the only place where Darwin uses war and battle as metaphors. In his chapter on the struggle for existence, he writes that “battle within battle must ever be recurring with varying success . . .” (p. 71). In the discussion of sexual selection, he refers to “the law of battle,” according to which males of most species must use their “weapons” to fight for access to females (p. 84). Remember the pachycephalosaurs.

Just to be clear: there is absolutely nothing in the theory of natural selection that obligates us to think of it as involving war, or combat, or fighting. In familiar schematic form, all you need for natural selection is heritable variation in a population that makes some difference to survival or reproductive success. Darwin’s line about the “war of nature” is gratuitous. So why is it there? Of course predation is violent. But war and battle are, in the first instance, human activities. These metaphors are optional.

Darwin’s penultimate line looks a lot like theodicy. The war of nature is horrible and gruesome, but maybe it’s justified by its results—the “most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving.” Of course, that most exalted object is us. So our own human activity—war—is made to seem natural, because that’s what all other creatures have been doing all along anyway. But the war of nature is then supposed to be justified by the fact that it has produced “higher animals” like us that make war with each other.

It’s hard to see the grandeur in this view of things.

Further Reading

This post builds on some ideas about war as a metaphor that I developed in an earlier paper. There may also be a connection between seeing nature as a scene of constant warfare, and seeing ourselves as being at war with nature.

Some Questions About Dinosaur Feet

Who could have predicted the latest revision of dinosaur phylogeny? It turns out that the answer may have been literally under the dinosaurs' noses--to say nothing of the rest of their bodies--the whole time.

Read MoreSome Questions About Dinosaur Hips

Derek Turner writes . . .

A few weeks ago, the journal Nature published a paper arguing for a major revision of dinosaur phylogeny. You've probably seen it in the headlines. I’ll leave it to others to subject Matthew Baron, David Norman, and Paul Barrett’s phylogenetic analysis to careful scrutiny. (See this excellent piece by Darren Naish for some preliminary discussion.) But however things look when the dust settles, the paper has left me thinking a lot about dinosaur hips. And I have many questions, along with one modest philosophical argument to make.

The Old Picture

On the one hand, you have—or had?—your lizard-hipped (saurischian) dinosaurs. That group included all the big sauropods and their relatives, as well as the theropods. On the other hand, you have your bird-hipped (ornithischian) dinosaurs, including the iconic Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and Ankylosaurus, as well as all the hadrosaurs. The basic skeletal difference between the two is easy to discern.

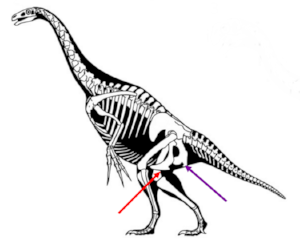

If you look closely at a skeleton of, say, an alligator, you can see the two pelvic bones called the ischium and the pubis. Although alligators aren't really lizards, they too have the reptilian "lizard hip" design. The bigger bone on top of the hip socket is the illium. The pubis kind of points forward and down, while the ischium sticks out behind. (As you can tell, I am not exactly a connoisseur here, but luckily, the morphology is so easy to perceive that even us philosophers can do alright. But see also Dave Hone's helpful discussion here.)

The skeleton of an alligator. The red arrow is pointing at the pubis, which is sticking forward, while the purple arrow indicates the ischium. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (though I added the arrows).

Now if you glance at the pelvis of a theropod dinosaur, or one of the big sauropods, they look sort of like the alligator pelvis, at least, in the sense that the pubis and ischium bones are pointing in different directions.

T. rex has a lizard-like hip joint, with the pubis (red arrow) pointing down and a bit forward, and the ischium (purple arrow) jutting backward. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (again, with the arrows added).

And here's Apatosaurus. Notice how the pubis (red) also juts forward, away from the ischium (purple). Image courtesy of wikimedia commons.

However, if you look at the skeleton of a modern bird, the hips look totally different. The ischium and the pubis bones are kind of smooshed together, with the pubis pointing backwards.

The skeleton of an emu. See how the pubis (red) and ischium (purple) both point backwards. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

The pelvis of a hadrosaur (one of the bird-hipped dinosaurs) looks more like the pelvis of a bird than like that of either a T. rex or an alligator. The pubis and the ischium bones are smooshed together and pointing aft.

A skeleton of Edmontosaurus. Note how the pubis (red) and the ischium (purple) are sort of smooshed together and pointing backwards.Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added). Also, in this dinosaur, there is a kind of bony flange sticking forward from the pelvic girdle, but that's a different structure, the anterior process, as Dave Hone explains here.

And for good measure, here's a Stegosaurus with the bird-hipped morphology. See how the pubis (red) and ischium (purple) are right up against each other. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

Until a few of weeks ago, the received view was that sometime back in the Triassic period, these two major branches of dinosaurs split off from one other and went their separate evolutionary ways.

The old dinosaur phylogeny that you probably learned as a kid.

But there was already something quite strange about this picture, even before Baron, Norman, and Barrett called it into serious question. We know that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs—that is, from lizard-hipped dinosaurs. So somewhere in there—probably in the evolutionary trajectory of small maniraptorans, which gave rise to birds—there was a major change in pelvic morphology.

Actually, the change from lizard hips to bird hips might have happened several times (even on the old picture): It may have happened independently in birds and dromaeosaurs (think of Deinonychus and Velociraptor). Those dromaeosaurs, weirdly, have pubis bones that point somewhat downward and backward, even though the shape of the pubis reminds one of T. rex.

This is Deinonychus--a weird case. It's a theropod, and so traditionally classified as saurischian, but the hip obviously looks kind of bird-like, with the pubis (red) pointing backwards and smoothed up against the ischium (purple). Compare it to the emu above. Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

And then there are the enigmatic therizinosaurs—another theropod group that also acquired a more bird-like hip construction. Why did these changes occur?

Another weird case. This is a reconstruction of a therizinosaur.. Therizinosaurs were theropods, hence saurischians (on the old picture), and yet they too seem to have had the pubis (red) smooshed up against the ischium (purple). Image courtesy of wikimedia commons (arrows added).

Another question: What sort of hips did dinosaurs start out with? Did they start out with lizard-like hips, or bird-like hips? Suppose, as seems likely, that they started out with lizard-like hips. That would mean that the transition from lizard-like hips to bird-like hips happened on one more occasion, in the ornithischian dinosaurs. (By my count, that’s as many as four distinct transitions from lizard hips to bird hips.) Or suppose the basal condition for dinosaurs was bird-like hips. In that case, you’d have an evolutionary zig-zag, with lizard-hipped dinosaurs evolving from bird-hipped ancestors, and bird-hipped birds evolving from lizard-hipped dinosaurs. Either way, there is quite a bit of explaining to do.

The New Picture

Baron, Norman, and Barrett argue that the old saurischian/ornithiscian classification gets things wrong, because it turns out that theropods are more closely related to ornithischian dinosaurs than to sauropods. They concluded this on the basis of a phylogenetic analysis of more than 400 characters, in dozens of dinosaur species from the Triassic and early Jurassic. Importantly, they looked at many characters that no one had previously fed into a phylogenetic analysis--and many details having nothing to do with the hip joint. (I am obsessing about the hip joints here, but they do not.)

The newly proposed phylogeny. Might have to rewrite all those dinosaur books.

According to this new picture, theropods and ornithischian dinosaurs together form a clade, now called the Ornithoscelida ("bird-limbed"). They keep the old name "saurischian" for the sauropods (or more precisely, the sauropodomorphs) together with another group, the herrerasaurs. [Note: this is a little confusing because, as we just saw, most theropods had lizard hips too. They now no longer count as saurischian, or "lizard-hipped"! But we shouldn't get too hung up on names. We could call the saurischians "Dino team A" and the ornithoscelidans "Dino team B" if we wanted to.]

Anyhow, the new picture suggests that the lizard-style hip construction is basal or ancestral for dinosaurs. In the early to mid-Triassic, when dinosaurs first evolved, and when the saurischians (sauropodomorphs + herrerasaurs) branched off from the ornithoscelidans (everyone else), everyone concerned had lizard hips. Then later on—possibly in the mid to late Triassic—the ornithoscelidans branched in turn into two groups. The theropods kept the ancestral lizard hips, though some of them would lose that morphology later on, when they evolved into birds, dromeosaurs, and therizinosaurs. But the ornithischians (for whom, sadly, the Triassic fossil record is pretty sparse) evolved the bird-hipped morphology pretty early on.

Some Questions About Dinosaur Hips

One striking thing about the proposed phylogenetic revision is that if we focus narrowly on the evolutionary history of one particular trait—the pelvic morphology—both the old and the new pictures provoke some of the same questions. Why, for example, did some lineages evolve the bird-hipped construction? And why did some groups, like the sauropods, retain the lizard-like construction for the long haul? Given that the hip structure changed in dromaeosaurs, why did it remain so stable in tyrannosaurs? And why do you see bird-hipped morphologies evolving from the lizard-hipped design, but (probably) not the other way around?

Some of the explanations that come readily to mind face obvious problems. For example, you might think that pelvic morphology has everything to do with locomotion. But then it’s hard to see why bipedal theropods and quadrupedal sauropods should have the same lizard-like hip morphology. Dinosaurs with a more bird-like hip construction also include both obligate quadrupeds (think of ornithischians like Stegosaurus) but also likely bipeds (maybe the dromaeosaurs, and—of course!—birds). So there just doesn’t seem to be any clear connection between this particular aspect of hip morphology and locomotion.

Another suggestion is that the bird-hipped construction, with the pubis pointing backwards, leaves more room for a larger gut. And a larger gut is a great idea for an animal that needs to digest big quantities of nutrient-poor plant material. This could well explain what was going on in the ornithischians, most of which were herbivores, as well as the therizinosaurs, which are now thought to have been an exceptional case of herbivorous theropods. But even this explanation runs into trouble: why did the ginormous sauropods retain their lizard-like hip construction? And why do you see more bird-like hips in the dromeosaurs, who were obviously carnivores?

Both the old phylogeny and the new revised one leave us with big (and as far as I know, largely unanswered) questions about why dinosaur hip morphology underwent evolutionary changes. How might scientists explore these questions further? One approach might be to study skeletal development in modern birds, so as to learn more about the developmental processes that generate the morphologies, but I'm not sure how promising that would be. If you have thoughts or speculations about how to address these questions, please feel free to share in the comments.

A Thought Experiment

There might be a further problem even with the way I've framed some of the questions above. I've been following tradition in characterizing dinosaur hip morphology as bird-like vs. lizard-like. I've also been thinking of evolutionary change as a change from one hip design to the other. But even a brief survey of the images above reveals that this is oversimplified. Dinosaur hips, including bird hips, vary in all sorts of ways. There are lots of evolutionary changes in hip structure that might not involve a shift from the lizard-like to the bird-like architecture. With that in mind, consider a thought experiment:

The Sheltered Paleontologist. Imagine a paleontologist who has somehow been sheltered from the world, and who has never had the opportunity to observe a bird or a lizard (or an alligator). But this scientist has made an extensive study, over the course of a whole career, of non-avian dinosaur hip joints. The sheltered paleontologist has studied every non-avian dinosaur hip so far extracted from the fossil record. Not only that, but the sheltered paleontologist has carefully mapped out the morphospace of non-avian dinosaur hip construction, with the aim of documenting trends and patterns in non-avian dinosaur hip evolution.

The sheltered paleontologist would not--could not--describe dinosaur hips as either bird-like or lizard-like. And so, when framing questions about the evolution of dinosaur hip morphology, the sheltered paleontologist would not fame them as I did above, as questions about the transition from a lizard-like to a bird-like design. The questions would have to be framed in some other way, relying on some other way of describing the skeletal features.

Since we can't observe dinosaurs directly, it's extraordinarily difficult for us to avoid using living organisms--birds and lizards, for example--as models for them. The thought experiment shows how this can affect even our descriptions of dinosaur morphology, and our decisions about how to individuate morphological characters. In writing this post, I actually set you up to "see" dinosaur hips a certain way, by first showing pictures of alligator and bird hips. Once you start seeing them that way, it's hard to get that distinction out of your head. But there is no reason, in principle, why anyone has to describe dinosaur hip morphology as bird-like or lizard-like.

So here's one last question about dinosaur hips: If the proposed revision to dinosaur phylogeny holds up under scrutiny, should the distinction between lizard-like hips and bird-like hips remain entrenched as a way of describing dinosaur morphology and framing evolutionary questions? If not, what should replace it?

Thanks

This post was inspired by a recent meeting of the paleontology reading group at the University of Calgary, where we discussed the new paper by Baron, Norman, and Barrett. Some of my questions about dinosaur hips are inspired by things that were said in that conversation. I'm grateful, and I hope I haven't botched anything too badly.

Reference

Baron MG, Norman DB, Barrett PM (2017), "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution," Nature 543: 501-506.

The Wilderness Before Time

Derek Turner writes …

Once I asked a class on environmental ethics how they would define “wilderness.” One student half-jokingly said that “wilderness is any place you can go, where other animals might eat you.” Anyone familiar with Werner Herzog’s film, Grizzly Man, will know that there is something right about this.

Timothy Treadwell, in Alaska's Katmai National Park. This does not end well.

My student’s comment contains an insight: wilderness is where we go to be reminded that nature doesn’t care about us, and that nature always has the last word.

What if the spiritual pull that draws us to dinosaurs is not that different from what draws us to Denali? Or to Alaska's Katmai National Park, which provided the setting for Grizzly Man?

Like Timothy Treadwell, the subject of Herzog’s film, some of the characters in Jurassic Park also get up close and personal with animals that can, and sometimes do eat them.

"Wilderness is any place you can go, where other animals might eat you."

Is there a connection between wilderness and paleontology?

Consider the following argument:

P1. Wild landscapes—places where humans have no permanent presence, and where human activities have relatively little impact—are especially valuable.

P2. Pre-human landscapes were wild.

C. Therefore, pre-human landscapes were especially valuable.

Let’s call this the WBT (“wilderness before time”) argument.

(I discuss some other possible connections between paleontology and environmental thinking in earlier posts, here and here.)

Is the WBT argument a good one? It is valid, meaning that the conclusion follows logically from the premises. But are the premises true?

The Prehistoric Wild

P2 looks to be in pretty good shape. The pre-human world was wild if anything is. Some have argued that no place on Earth today is truly wild, because human activities—especially the burning of fossil fuels—have altered every square inch of the planet.[1] However, the pre-human wild was the real deal, completely unaffected by anything that humans would ever do in the future. Because we cannot intervene in the past, we can do nothing to “tame” or “civilize” the pre-human wilderness.

Troubles with The Wilderness Concept

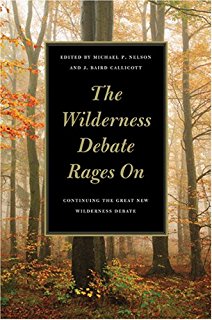

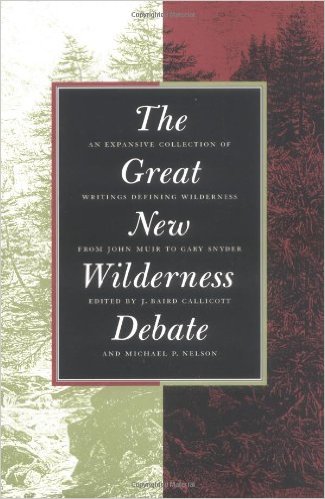

P1 is more questionable. Many environmental thinkers in North America, at least since John Muir, have held that wild places have special (possibly intrinsic) value. There have been many efforts to get clear about the value(s) of wilderness, and the literature on this issue in environmental ethics is vast.[2] Speaking autobiographically, though, reading William Cronon’s classic essay, “The Trouble With Wilderness,” has made it very tough for me to get behind P1.[3]

Perhaps the most serious problem (though by no means the only one) concerns the often violent history of mistreatment and displacement of Native American and First Nations communities. In North America, many of our cherished “wild” places are landscapes that people had lived in and loved and modified and been modified by for a very long time before disease-bearing Euro-American settlers showed up. In some cases, newcomers forced Native people out and subsequently declared those places “wild,” as if they had always been empty, or as if the people living there were less than human. The idea that such areas are untrammeled by humans is a mythical smokescreen that hides a history of injustice. It’s hard to see how to treat wilderness as an anchoring environmental value without confronting this history.

Gratuitous wilderness shot, from a backpacking trip in the Sierra Nevadas, at Thousand Island Lake in the Ansel Adams Wilderness.. Does the human presence mar the scene?

Another problem with P1 is its negative anthropocentrism. The idea that something has value in virtue of the fact that humans have not interacted with it implies that human interaction with something diminishes the value of that thing. Hence the injunction to "leave no trace" in the wilderness. But that’s just as arbitrary and unmotivated as positive anthropocentrism, the view that membership in a particular biological species confers special moral status. One could just as well define “wilderness” as any place that’s unoccupied and untrammeled by some other nonhuman species—any place untrammeled by squirrels, for example.

There is much, much more to be said here, but these are two main reasons why I hesitate to defend P1. When it comes to fundamental environmental values, it might be more helpful to talk about biological diversity, or ecological health, or sense of place, or the value of individual living things and biological relationships.

Nevertheless, wilderness can exert a profound pull, even upon those of us who are more than a little skeptical. We go—at least, those who are lucky enough to be able to afford the cost of transportation and the expensive backpacking gear—in order to be humbled and perhaps tested. We go to be reminded that nature, like the gods of the ancient Epicureans, is utterly indifferent to human life and well-being.

So the WBT argument is valid, and P2 is true, but P1 is problematic. I’m therefore not sure we should buy it. But let’s think about what the argument might mean for paleontology.

Paleontology and the wild, Pre-Human Past

It’s no coincidence that paleontology started to capture the American imagination in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at precisely the moment in American cultural history when people like John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt begin to lament the “closing” and the “taming” of the North American wilderness. The wilderness preservation movement was born of nostalgia: The distinctive American character was forged in the process of developing and cultivating the wild frontier—or so went the story told by Frederick Jackson Turner and others—and we need to preserve remaining wild places so that people can continue to have those formative experiences. At the same time that the federal government was establishing national parks—Yellowstone in 1872, Yosemite in 1890, followed by many others—wealthy philanthropists were establishing museums in New Haven (1866), New York (1869), Chicago (1893), and Pittsburgh (1896), institutions whose mission was to give people a window on a prehistoric wilderness that really was untrammeled, and where lots of animals would have been happy to eat you or crush you underfoot.

The WBT argument suggests that paleontology might have, in addition to various epistemic goals, the non-epistemic one of putting us in touch with pre-human wilderness.

The scientific effort to reconstruct the deep past is, perhaps in part, a kind of cognitive backpacking trip—a way of visiting a landscape, one displaced from us in time rather than in space, and one whose value depends on the fact that humans do not belong there. The joys of paleontological reconstruction may derive in part from the promise of access to wilderness. This points to another way in which the scientific study of the deep past is suffused with the values of the broader culture (See Joyce’s great discussion that issue here.) Perhaps we feel impelled to reconstruct prehistoric landscapes because they have value qua wilderness.

The familiar epistemic goals of historical natural science blend with nostalgia for wild places that are increasingly hard to find.

In an earlier post, I suggested that dinosaurs might be overrated, in the sense that their high cultural profile is out of proportion to their scientific importance. Why, for example, is it more important to figure out the colors of the dinosaurs than to figure out why the ammonoids had such high speciation and extinction rates?[4] The WBT argument, together with my student’s observation, goes some way toward accounting for this. Perhaps we want to do our cognitive backpacking across prehistoric landscapes where some of the animals could eat us.

[1] One person who made this point relatively early was Bill McKibben, The End of Nature, Random House, 1989.

[2] See especially the papers collected in The Great New Wilderness Debate, edited by J. Baird Callicott and Michael Nelson, University of Georgia Press, 1998, as well as The Wilderness Debate Rages On, edited by J. Baird Callicott and Michael Nelson, University of Georgia Press, 2008.

[3] William Cronon (1995) “The Trouble with Wilderness, Or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. New York, W.W. Norton, pp. 69-90.

[4] M.M. Yacobucci (2016), “Towards a model for speciation in ammonoids,” in Species and Speciation in the Fossil Record, edited by W.D. Allmon and M.M. Yacobucci. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 238-277.